Are There Health Consequences to An Anti-Immigrant Climate for Undocumented Immigrants?

[Editor’s Note: This is the fourth and final blog post in a series on Words Matter, our campaign on the impact of anti-immigrant rhetoric, written by Kaethe Weingarten, PhD, Director of Witness to Witness here at Migrant Clinicians Network. The first three parts are on common immigration narratives, the health impacts of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, and the mental health toll of gun violence on immigrants. Access practical resources and sign up for monthly updates from Dr. Weingarten on the Witness to Witness page. And, most importantly, consider donating to support the upcoming webinar series that Dr. Weingarten and her team are offering to clinicians, to help them better understand and serve their immigrant patients, which will in turn support the health and well-being of immigrants across the country. Please read our note below regarding “undocumented” terminology in this blog.*]

Attitudes in the United States toward immigrants have varied across centuries, with policies and rhetoric following and shaping prevailing attitudes. Today’s attitudes vary widely. Many politicians, commentators, and scholars have written that the people who are coming to the US border are fleeing injustice and conflicts in their home countries, leaving due to fallout from COVID, and coming to the US because Europe has made immigration there more difficult. This current pattern follows decades of migration responding to political turmoil and economic decline. Still more people are fleeing due to climate-related disaster. There are multiple counter narratives as well. Many people believe that the people who flee their home country do so because they are not wanted there; they are criminal or mentally unfit. Others believe that immigrants deprive citizens of what is rightfully theirs, jobs or health care or space in schools. These counternarratives make no distinction between documented and undocumented immigrants. In most parts of the globe, the plight of undocumented immigrants is particularly harsh.

In this blog, I will be looking at the health consequences for one category of immigrants, undocumented immigrants for whom access to health care and health outcomes is severely impacted by the negative environment towards immigrants that has been ascendant in the last several years in many parts of the world. An undocumented immigrant is defined as a person who:

- Legally entered the county but overstayed their permit to be here;

- Received a negative decision on their asylum claim and stayed;

- Remained in the country after having their residency permit rejected;

- Entered the country using fraudulent documents; or

- Unlawfully entered the country or was smuggled in.

In a systematic review of the impact of immigration policies on the health status of undocumented immigrants, the authors note that “[u]ndocumented immigrants have often experienced multiple pre-and-post migration stressful events, including imprisonment, rape, ethnic cleansing, physical violence, economic distress, torture, and many others. These unique challenges make them prone to higher rates of morbidity and mortality.”

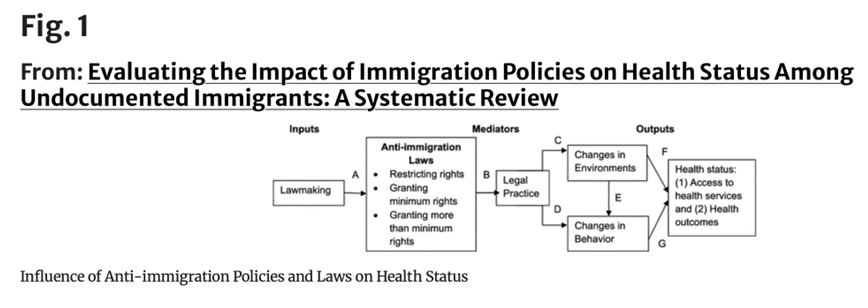

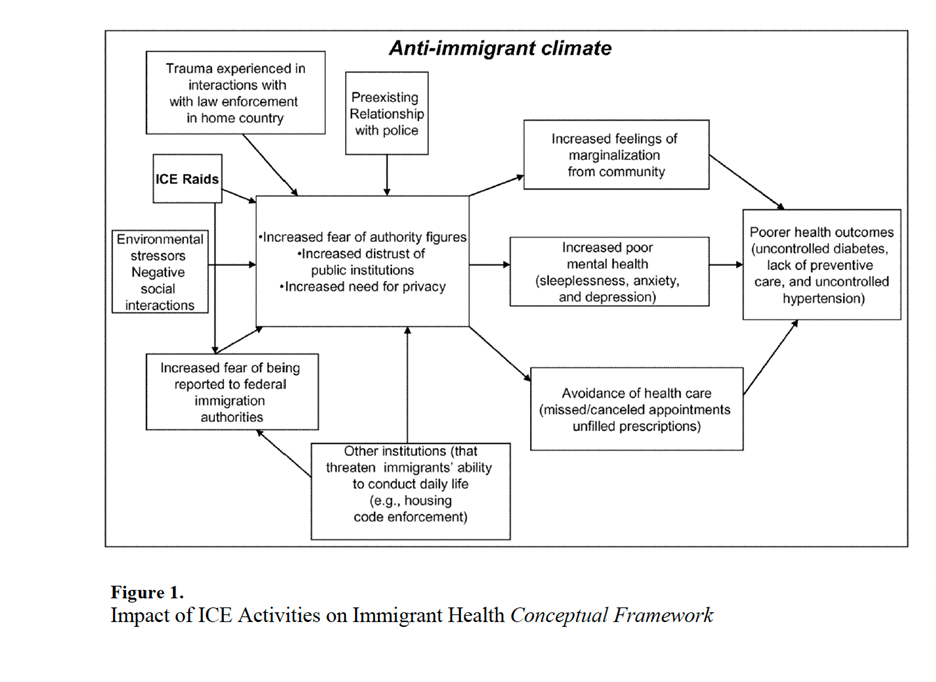

In this same article, the authors present a Figure to show graphically the pathways by which immigration laws and policies lead to less access to health services and poorer health outcomes. A key word in the graph’s analysis is “environment.” In this case, the authors are referring not only to the physical environment but also to the “social structures and institutions,” such as both private and federally funded health clinics that either increase or decrease resources, expand or reduce rights. People respond to the changes, with some behaviors being adopted to minimize the perceived threat to their staying in the host country, often at the cost of not accessing needed health care. These different behaviors lead to changes at population-level health outcomes of illness and death for undocumented immigrants.

While the analysis above provides a conceptual framework, research bears out the model. One study of 20,211 adults and children in a single-center health care system found a 43.3% decrease in primary care visits by undocumented children and a 34.5% decrease in completed primary care visits by adults between 2015 and 2018, during a period when anti-immigrant rhetoric was high. There was a Medicaid control group and this group with documented status did not have a significant decline in health care utilization.

In a study conducted in Everett, MA in 2009, community partners and researchers used six focus groups with 52 immigrants who spoke five languages, both documented and undocumented, to learn from the participants’ direct experience what it is that most worried them in relation to utilizing health care services. They were able to distill their findings into a figure also, this one more nuanced than the one above but revealing very similar patterns:

"The major themes across the groups included: 1) Fear of deportation, 2) Fear of collaboration between local law enforcement and ICE and perception of arbitrariness on the part of the former and 3) Concerns about not being able to furnish documentation required to apply for insurance and for health care. Documented and undocumented immigrants reported high levels of stress due to deportation fear, which affected their emotional well-being and their access to health services.” The perception that they faced deportation or harassment from authorities correlated to not utilizing health services. The researchers found that the perception matched reality: “We found that institutions such as law enforcement agencies and health care establishments discriminated against undocumented immigrants.”

Of the total population of immigrants in the US, 11 million, or 23%, are undocumented immigrants. Also, of the 11 million undocumented immigrants, about 72-76% are Latinx, mostly coming from Mexico and Central American countries. In a study conducted for Migration Policy Institute, Cecelia Ayón carefully defined discrimination towards Latinx immigrants. She defined it as: “Discrimination involves harmful actions, often based on prejudice, towards members of particular groups or nationalities; these harmful actions often involve denying these members equal access to resources and opportunities. Discrimination is observed at both the individual level, in daily interactions with community members, and at the structural or institutional level. The sociopolitical climate around immigration may be used to legitimize the poor treatment of immigrants, regardless of their actual legal status.” She then points out that discriminatory behavior on the parts of providers and institutions leads to avoidance of these institutions for fear of being detained or deported, thus leading to negative outcomes for the physical and mental health and well-being of immigrant families.

A number of studies have pointed out that the presence of anti-immigrant rhetoric impacted health care providers’ attitudes and behaviors, with jurisdictions with stronger anti-immigrant policies discriminating more than in jurisdictions with less harsh rhetoric. Of note, this correlates with the prevalence of mental health outcomes. In jurisdictions with neutral or welcoming policies towards immigrants, for instance in “sanctuary cities,” the rates of negative mental health outcomes are lower.

As this review article summarizes, “undocumented immigrants living in environments where they fear deportation owing to restrictive policies are less likely to access health services, are less able to comply with health providers’ recommendations, and experience higher levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety than do their documented counterparts. Increased police and immigration surveillance also result in decreased mobility for undocumented immigrants, disrupting their ability to seek employment, maintain social relationships, and access public services and spaces….This chronic anticipatory stressor can lead to social isolation, limited access to health and social services, and economic uncertainty.” Of note, the fear and uncertainty that undocumented immigrants experience is not theirs alone, for it impacts their friends and family members as well. Thus, researchers are finding that rates of mental health difficulties are rising in the Latinx community more widely, and these rates increase with the number of years of living in the US. In one review article, the impact of uncertainty around DACA status was seen to contribute to mental health issues, although it should be noted that in this same review, resilience factors for this group were also detailed, in particular the motivation to live each day “luchando adelante” [moving forward].

State-level enforcement of policies limiting the rights of undocumented immigrants varies across the 50 states. This map gives a good visual image of the range. “States are closely divided between protective laws (12 states with a combined population of 112 million people) and harmful laws (18 states with a combined population of 127 million people), with 24 states that have not yet passed sanctuary or anti-sanctuary policies (with a combined population of 93 million people). More foreign-born residents are impacted by states with protective laws (23 million people) versus states with harmful laws (14 million people), with eight million people residing in states that have passed no laws on immigration.” Undocumented immigrants and their family members are less likely to have mental health issues and are more likely to utilize health care resources in locales where local law enforcement does not participate in deportations.

Conclusion

More research is need on the experience of undocumented immigrants and yet this is difficult to collect. Undocumented immigrants have good reason to be concerned about providing information to officials, be they government representatives or academic researchers. Several authors point out that research is likely to be more accurate if researchers collaborate with trusted community groups serving this population. It is also difficult to investigate questions over time since undocumented immigrants must often change residence or phone numbers to avoid immigration enforcement. Contact through social media may be more stable.

Advocacy efforts are crucial to make the lives of undocumented immigrants less precarious and to provide the kinds of protections that will allow them to access needed physical and mental health care. It’s possible for state and local governments to pass regulations that mitigate federal policies, for instance by allowing those with undocumented status to obtain identification or a driver’s license. Some locales declare that they are sanctuary cities, preventing local law enforcement from cooperating with immigration enforcement, allowing immigrants to feel safer to move freely within their communities. Professionals in the health care and public health arena can advocate for these changes.

In one study of 24 health care providers in a progressive community, researchers interviewed participants to understand the barriers to care and the solutions to these barriers. The dominant barrier was the fear experienced by undocumented immigrants relative to policies at the federal, state, and local levels, and institutional barriers such as inadequate interpretation and culturally mis-attuned care. Providers reported a number of practices that mitigated the fear, including community partnerships, clinics embedded within the community, and community member empowerment.

In sum, people utilize health care services where access is not prohibited to them and where they feel safe. Safety hinges on trust at all levels. Research strongly suggests that community partners with similar populations are most likely to mitigate fear in undocumented immigrants. Clinicians can advocate within their institutions for their executives to support collaboration with community groups to better serve vulnerable undocumented immigrants.

*Terminology note: Migrant Clinicians Network typically refers to those who are in the United States without legal authority as “unauthorized” as opposed to “undocumented.” Many of these immigrants have forms of documentation of their lives, journeys, and applications, but may not have a formal immigration status or may have a fluctuating immigration status. However, much of the research that Dr. Weingarten relied upon to write this blog post referred to this class of immigrants as “undocumented.” For the sake of clarity, we are retaining the references to “undocumented” immigrants throughout the piece.

- Log in to post comments