The Mental Health Toll of Gun Violence on Immigrant Communities

Witness to Witness is taking a stand against anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies with an impactful campaign featuring a compelling three-part webinar series for clinicians. Support this important work: https://www.migrantclinician.org/donate/w2w

Note from Dr. Weingarten: This blog, the third in a series (read part one and part two) on anti-immigrant rhetoric, was written before the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump. I can only hope that the experience of terror will increase empathy for others who fear gun violence. Many organizations, like Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action, and Everytown pursue gun safety in the US. Advocacy for gun safety is an action we can take to protect the health of all communities.

A climate of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies has significant negative effects on immigrant physical and mental health, as I have laid out in the first two articles in this series. The mechanism that produces these negative health effects is likely related to chronic stress.**

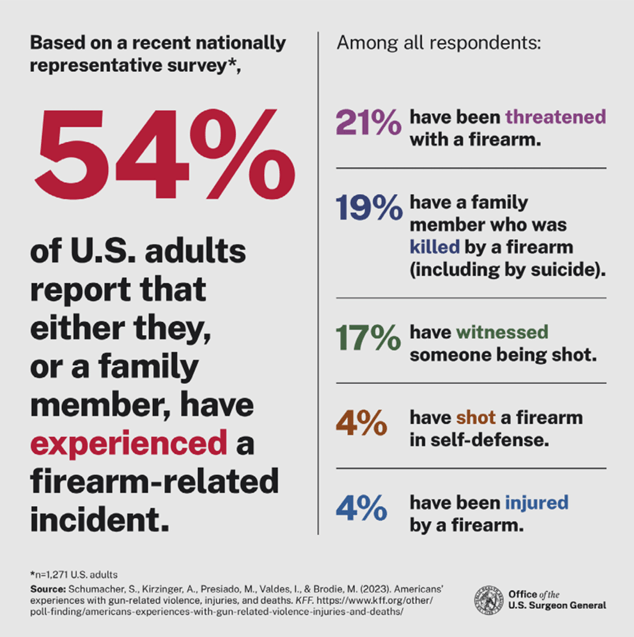

One particular source of fear and worry that is impacting Latinx communities is gun violence. A June 2024 KFF data analysis found that firearms played a role in 79% of homicides and 55% of suicide deaths. That same month, the Surgeon General of the United States issued an Advisory related to firearms. There are many eye-popping statistics in the Advisory. For example, in 2015, firearm-related deaths were 11.4 times higher in the United States than in 28 other high- income countries. Children and youth rates of suicide in the US have skyrocketed , which is likely related to firearm access. Although mass shootings account for only 1% of firearm death, they are a significant source of fear for the public. More than three-quarters of US adults say they fear a mass shooting and about one-third of adults say they avoid going to certain places out of fear of a shooting.

The Advisory also makes clear that firearm deaths are not distributed equally. Due to “structural, institutional and individual racism” there are inequities in exposure to firearm violence. “Racial and ethnic minority population groups are more likely to live in neighborhoods with concentrated economic disadvantage due to economic setbacks, historic divestment, and harmful discriminatory policies like redlining. In 2020, counties with the highest levels of poverty experienced firearm homicide rates 4.5 times as high, and firearm suicide rates 1.3 times as high, as counties with the lowest poverty levels.”

Katelyn Jetalina, PhD, who writes a popular blog with a sign off, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” underscores the impact on communities of gun violence, which, due to the impact of witnessing, even one shooting can impact as many as 200 people. She also reproduces a figure from the Advisory I also found illuminating. It shows the “ripple effects” on hundreds of people from one shooting in a single neighborhood.

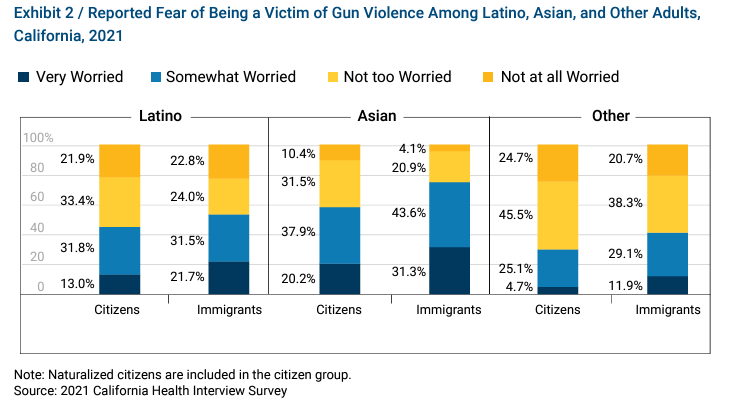

Research clearly shows a relationship between owning guns and death from firearms. Safe storage strongly mitigates this relationship. However, rates of gun ownership vary by race/ethnicity. In one study in California by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, comparing Latinx and Asian groups to all California adults, the researchers found significant differences. Here are some of the more interesting findings.

- 17.6% of all California adults own a firearm but only 4.1% of Latinx and 7.2% of Asian immigrants do.

- Three-quarters of Asian immigrants and half of Latinx immigrants report being “very worried” or “somewhat worried” about being the victim of gun violence.

- Latinx immigrants who were very worried about gun violence had fewer guns than Latinx citizens who were not too worried about gun violence.

- In general, immigrants were more likely than citizens to store guns safely, locked and unloaded.

Many factors likely account for the fact that immigrants are more worried than citizens about being the victim of gun violence. Immigrants may be implicitly or explicitly connecting that those who are strongly fearful of immigrants without authorization are the same who denounce gun restrictions, and may make conclusions that those who strongly oppose immigration are the same who own guns and may wish to use them against immigrants. For example, Chapman University has been conducting surveys on American fears, worries, and concerns since 2014. In 2022, the University conducted an opinion survey via the web with 1,020 adults ages 18 and older. Of the people who say they are “afraid” or “very afraid” of illegal immigration, 68.94% are “afraid” or “very afraid” of restrictions on guns or other types of firearms. By contrast, of those who say they are not afraid of illegal immigrants, only 14.9% are “afraid” or “very afraid” of firearm restrictions. When the question is posed more broadly, a very high percentage (83.33%) of people who say they are afraid of immigrants responded that they are “afraid” or “very afraid” of gun restrictions.

In a twist to the perception of threat, researchers have also documented a link between guns and immigrants but in the opposite direction of what is explicitly feared. In a review of a recently published book, Exit Wounds: How America’s Guns Fuel Violence Across the Border by Ieva Jusionyte, Ruth Conniff summarizes the book’s thesis. While the US government spends enormous time and energy policing the Northward flow of guns, drugs and people, it does very little to stem the flow of these into Mexico. In fact, Jusionyte reports, gun traffickers carry one-quarter of a million guns down to Mexico every year. It is these very guns, wielded by drug cartels, from which so many people traveling from Mexico are fleeing. “Somehow we fail to connect the dots: that the violence people are fleeing, the violence we are afraid they would spread in the United States is, in large part, of our own making,” Jusionyte writes. How ironic, then, that Latinx immigrants who fear for their lives, are seen by some American citizens as being the dangerous ones!

I will mention one other domain that may also account for the fear that Latinx immigrants have that they may become victims of gun violence. Gun violence accounts for tens of thousands of deaths every year and also costs the health care system more than $1 billion in medical costs. But these costs are not evenly distributed across regions of the US. From 2016 to 2017, the South accounted for 44% of total firearm-injury-related hospital costs, the region where most (42%) Latinx immigrants live.

Clinicians can take practical steps to help reduce the fear that Latinx immigrants experience around gun violence:

- It’s important that clinicians validate the experience that many of their Latinx patients are likely to be having. This may be an opportunity that occurs spontaneously because your patients tell you that they have these fears, or it may be something about which a sensitive inquiry will help patients talk about their fear and worries.

- Clinicians can educate patients about the health consequences of chronic stress. This should always be done in the context of offering verbal suggestions and culturally and linguistically appropriate handouts of steps they can take individually to decrease stress. There are many good handouts available. The Witness to Witness program has good resources here and Mental Health America has a toolkit specifically for BIPOC mental health. However, individual attention to diminishing stress is not going to alter the conditions that produce it. Clinicians may want to know about local community groups that advocate for policies that are less harsh towards their Latinx patients.

- Clinicians can testify to the mental and physical negative health consequences of hostile rhetoric and harsh public policies. They can lobby policymakers on the risks associated with anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. Excellent one-page infographics that can help make the case to policymakers have been developed by the Culture & Mental Health lab at Utah State University under the direction of Melanie M. Domenech Rodríguez. They are freely available here and here.

- Finally, clinicians can advocate for limiting access to guns, particularly military-style semiautomatic weapons and sniper rifles and ammunition, as a serious health threat to patients of all demographics.

Everyone deserves to live without fear and to be seen as a safe person, not someone to fear. The Witness to Witness (W2W) program is doing our part by carrying out an ongoing campaign to draw attention to the impact of negative rhetoric and restrictive policies on immigrants. You can follow our campaign at #WordsMatter. Please help us spread the word and support the campaign with a donation to help us develop resources and webinars to train clinicians on anti-immigrant rhetoric and how to respond. As we say at W2W, reasonable hope is something we do together.

**The link between chronic stress and poor health among immigrants is strong. One study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America said: “Numerous studies demonstrate links between chronic stress and indices of poor health, including risk factors for cardiovascular disease and poorer immune function. Nevertheless, the exact mechanisms of how stress gets ‘under the skin’ remain elusive. We investigated the hypothesis that stress impacts health by modulating the rate of cellular aging.” They found that women “with the highest levels of perceived stress have telomeres shorter on average by the equivalent of at least one decade of additional aging compared to low stress women. These findings have implications for understanding how, at the cellular level, stress may promote earlier onset of age-related diseases.”

Lest any reader think a distinction is being made between perceived stress and actual stress, this excerpt from a recent literature review may be helpful: “The psychological stress associated with anti-immigrant rhetoric and ever-changing policies is undeniable, with mounting evidence indicating that immigration-related stress is associated with poor mental health, including anxiety, trauma, and depression among Latinx immigrants. Exclusionary immigration policies (ie, those that limit opportunities and resources), as a form of structural racism (ie, macro-level conditions [residential segregation and institutional policies]), have also led to an epidemic of stress-related health within the Latinx community, particularly the Latinx immigrant community, across the country.”

- Log in to post comments