Words Matter: The Health Impact of Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric and Policies, and What Clinicians Can Do

[Editor’s Note: This is the second blog post in the two-part series on the health impacts of negative immigration rhetoric offered by Kaethe Weingarten, PhD, the Director of Witness to Witness here at Migrant Clinicians Network. Read the first blog post, “Common Immigration Narratives and Their Distressing Effect.” Be sure to stay tuned: Dr. Weingarten and her team will be fundraising during July (BIPOC Mental Health Month) to provide training and resources to clinicians on this very important and timely topic.]

“The 2024 election cycle is in full swing and along with it is a steady stream of rhetoric against immigration and immigrants themselves. For those of us who work with immigrants, whether or not we are immigrants ourselves, the drum beat of hurtful statements is appalling.” – Kaethe Weingarten

“Conflating people seeking refuge with people who have mental illness and depicting immigrants and refugees as people from ‘mental institutions, terrorists’ is the worst form of stigmatization. It should be called out for what it is: old-fashioned bigotry.” – Rob Walters, MindSite News

Hateful immigration rhetoric has significant negative health consequences for immigrants – and, following recent polls on public opinion and the tenor of the election thus far, we can expect this demeaning rhetoric to heat up, posing physical and mental health risks. For this blog post, I reviewed dozens of research articles and recent polls to synthesize what’s happening in this current moment in terms of political rhetoric, policy, and enforcement, and what we know about their health consequences for immigrants, particularly Latinx immigrants.

Has political rhetoric in general gotten more negative?

The public feels that it has. Already in 2019, a Pew Research Poll of a representative sample of US adults found that “more than eight-in-ten US adults (85%) say that political debate in the country has become more negative and less respectful” than in the past. In a follow up to this finding, researchers applied psycholinguistic tools to 24 million quotes from online news between 2008 and 2020 attributed to 18,627 US politicians. Their findings were published in 2023 and they found that a rise in negative language occurred sharply across parties with the 2016 campaign, particularly among prominent speakers. They wrote: “With the 2016 campaign, a more general mood of partisan polarization in the country was both reflected and amplified.”

Additionally, public opinion is becoming more negative towards immigrants who lack authorization to work in the US. According to a June 8 poll, Pew Research found that the share of registered voters favoring allowing such immigrants to stay in the US had dropped from 77% to 59% and the share of registered voters who say they should not be allowed to stay has nearly doubled. These numbers suggest that the rhetoric about immigrants harming the economy is gaining headway, when in fact, economic data shows that immigrants benefit the US economy.

How does negative rhetoric in general affect the health of immigrants?

The impact of partisan polarization is not just a political issue but as researchers point out, it is a public health matter as well. In one study, respondents reported that their exposure to politics has had a negative impact not only on their physical health but also on their emotional well-being, for instance, causing them to lose friendships. Research shows that political polarization affects people with poor physical health the most. Polarization occurred in many communities specifically about policies that should or should not be in place to mitigate COVID. It turns out that people are more subject to negative health effects if their views diverge from the majority opinion in their community. For immigrants in states with anti-immigrant policies, one would then expect more negative health impacts than for immigrants living in states with more inclusive policies. This turns out to be the case.

How does negative rhetoric around racism specifically affect the health of immigrants?

One of the proposed mechanisms for the negative effect is that exposure to politics “is a unique chronic stressor in the environment and that people who are not particularly stressed or anxious about other parts of the social environment still seem to get stressed and anxious about politics.” It seems that these effects are not evenly distributed. A review article from 2013 concludes that despite “marked declines in public support for negative racial attitudes,” racism negatively impacts the physical and emotional health of historically marginalized communities in many ways. The authors note that “experiences of racial discrimination are an important type of psychosocial stressor that can lead to adverse changes in health status and altered behavioral patterns that increase health risks.”

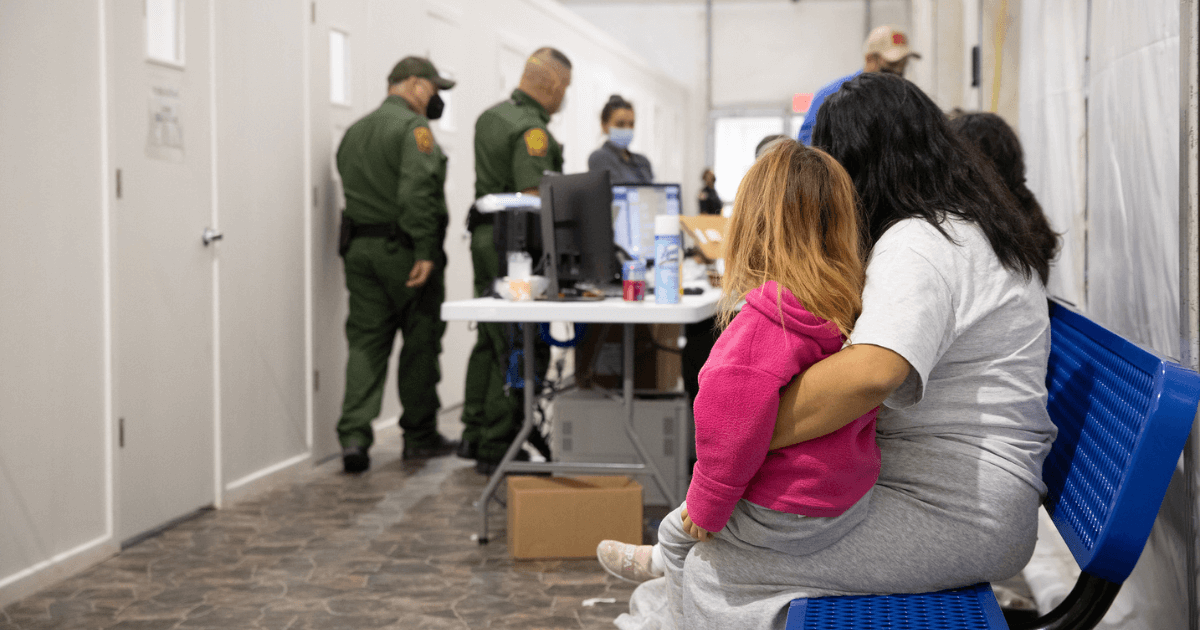

How do restrictive immigration policies and enforcement affect the health of immigrants?

In 2012, a first-ever research study was conducted in 31 states to examine the mental health impact of state-level legislation. The authors identified policies in four domains: immigration, race/ethnicity, language, and agricultural worker protections. They found higher rates of poor mental health days in Latinx participants living in states with more exclusionary policies. The results were specific to immigration policies in the state not to the overall political climate or residential segregation. The authors conclude that “restrictive immigration policies may be detrimental to the mental health of Latinos in the United States.”

Given the many states where restrictive policies target immigrants, it is no wonder that when faced with these threats and deprivations immigrants regardless of their legal status in the US experience toxic stress. So pervasive are these effects that a scale has been developed to capture them, called the Perceived Immigration Policy Effects Scale (PIPES). The author, Cecelia Ayón, writes: “The measure was developed in Spanish to assess the impact of state-level immigration policies on Latino immigrant parents.” In many instances, parents who are undocumented fear that their lack of legal status poses a risk to their children not just of deportation itself but fear of parental deportation. This is borne out by research conducted by Valdez and her colleagues. They have modified the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACEs) framework to include immigration-related adversities that can be “traced back to immigration policies and/or enforcement practices” at the macro-systemic level, that is, the broader socio-political environment level.

Building on the Immigration-Related Adverse Childhood Experiences Model as noted above, one study found an association between immigration enforcement fear and PTSD among first and second-generation Latinx youth in immigrant families. Due to the fact that Latinx individuals often belong to a larger extended family and are connected to people in their community and neighborhood, restrictive policies that affect friends and family but not them personally can also be stressful. In one study, the authors asserted: “We contend that immigration-related discrimination is not limited to individual experiences but rather is shared within the family and community, with negative implications for the mental health of undocumented immigrants and mixed-status family members….Our qualitative findings reveal that immigration-related discrimination and the impact that these experiences have on mental health are not limited to individual experiences. Rather, it operates within the family and even extends to community-level experiences through vicarious discrimination.” What these authors call vicarious discrimination fits with our Witnessing Model, a model I developed in the 1990s. Being a witness confers a similar level of risk of psychological harm as being the victim of violence or violation itself.

Negative rhetoric aimed at immigrants, restrictive policies towards immigrants and harsh enforcement policies targeting immigrants combine to create a toxic brew. Whether one is an immigrant oneself or knows someone who is, these conditions create a hostile environment for a wide of community of people.

Taking it all together: How does negative rhetoric around immigrants affect the health of immigrants?

Numerous research studies arrive at similar conclusions to this 2022 study: “Escalating xenophobic political rhetoric, proliferating policies restricting migration, increased interior enforcement, and regulatory changes impeding resource access all contribute to a hostile environment for immigrants that is detrimental to adults and children.” This is impactful on huge numbers of children, one quarter of whom are growing up in US immigrant families. The chronic stress and deprivation that stem from these conditions produce toxic levels of stress that last a lifetime for children and adults alike. In an article published in 2017, the same point is made: there are “negative health effects on people who have been direct targets of what they perceive as hostility or discrimination and on individuals and communities who feel vulnerable because they belong to a stigmatized, marginalized, or targeted group.” Very little has changed since those words were written. The authors put forward a range of suggestions as to how health care providers can respond to the toxic stress that affects immigrants and others in groups targeted by hostile rhetoric and policies. The following points are based on suggestions gathered from the articles I have linked to.

- As I wrote in the May blog, clinicians need to ensure that health care spaces signal that all people are welcome and that care is delivered to all regardless of citizenship status. Health care facilities may also want to create fliers that direct patients to local resources that assist immigrants, including community advocacy groups.

- It is crucial that clinicians be informed about the current policies that are in effect nationally and at the state level that may have an impact on their patient population. Being informed about local goings-on like billboards, protests or community gatherings, or, more broadly, social media campaigns, is important. It may be useful to set aside time during staff or team meetings to share information about facts and rumors circulating in the community.

- Clinicians can listen compassionately to their patients if and when they reveal their distress. However, it is also likely that some patients will be afraid to broach the topic themselves. Clinicians should be prepared to open the topic, inquiring whether the patient has been impacted by discrimination or hostility. In doing so, the clinician has an opportunity to demonstrate awareness about the stressful environment their patient faces as well as normalizing the patient’s response to it.

- At the same time, caution must be observed not to expose patients to risks associated with disclosure of fear, threat, and discrimination. That is why it is imperative to understand the institution’s reporting requirements and to make these crystal clear to patients before conversations on these topics take place.

- While it is important to listen to patients’ fears and concerns, it is equally important to ask questions that help patients access their strengths and hopes for a good future.

- Primary care providers and community health workers need to know the specific programs within the health care system and in the community that are available to support immigrant patients. For instance, Valdez and her co-authors developed Fortalezas Familiares (Family Strengths), a culturally and linguistically tailored family-focused resilience intervention for Latinx immigrant mothers with depressive symptoms, other caregivers, and children ages 9–17. This type of program explicitly links individual distress to the broader socio-political environment that produces the stressors, including pre- and post-immigration experiences, thus de-pathologizing an individual’s suffering and “normalizing” it.

- Finally, Falicov has put forward a comprehensive framework, MECA, Multidimensional-Ecosystemic-Comparative Approach, that is useful for all clinicians in working with patients, to see them as complex human beings who are impacted by many factors, of which the immigration experience and sociopolitical stressors are key.

All of the suggestions above are ones that a provider can take in the “office.” None of these will create change where it is most needed, at the federal, state and municipal levels. For change to occur, all of us must advocate for policy change, including speaking out about the pernicious effects of demeaning political rhetoric. At a recent rally, a leading candidate for election said this: Immigrants “are changing the fabric of our country. They are destroying our country. They are doing things that are unthinkable.” This language is untrue and unacceptable. Far from destroying our country, immigrants are vitally needed. The reality is that the US desperately needs immigrants to keep the economy growing. Many industries, like construction, agriculture, and long-term care, need more workers. With declining fertility rates and an aging US population, more workers are needed. New data released in June confirm what FBI data has reported, namely that there have been dramatic decreases in both violent and property crimes. Other research shows that “immigrants are 30 percent less likely to be incarcerated than are U.S.-born individuals who are white.”

But beyond that, everyone who arrived here, whether thousands of years ago, hundreds of years or one week ago, is an immigrant to this land mass. Immigrants have always contributed to this country; we are foundational to the country’s strengths, past and present. Health care providers have a role in mitigating the negative effects of degrading rhetoric, restrictive immigration policies and harsh enforcement practices in their individual encounters with their patients. And, of equal importance, all us, health care providers too, need to be strong and persuasive advocates for change.

- Log in to post comments