After Hurricane Beryl: Five Practical Considerations for Health Centers Serving Migrants and Immigrants in a Climate-Infused World

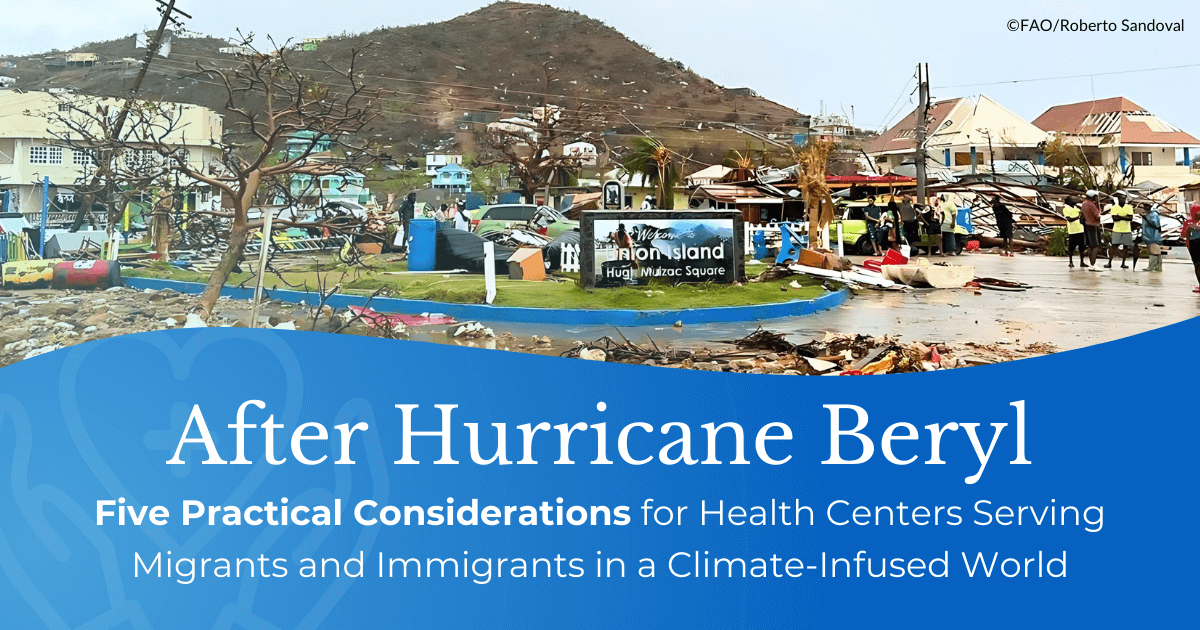

When Hurricane Beryl pummeled the Caribbean with wind speeds of 160mph earlier this week, it became the earliest category-five Atlantic hurricane on record. Disturbingly high sea surface temperatures – a feature of climate change – are believed to have made the storm so powerful, so early in the year. Beryl broke another record: it moved from a tropical depression to a hurricane in record time, just 42 hours. “Unprecedented as Beryl is, it actually very much aligns with the kinds of extremes we expect in a warmer climate,” Andra Garner, an assistant professor at Rowan University in the US, told the BBC.

The health consequences of this hurricane have been widespread, in part because its early presentation aligns with July weather, instead of the cooler September or October weather typical for a storm this severe. In Houston, three days after Beryl, a million people still lack power while an extreme heat wave grips the region. Houston-area hospitals are overrun, as providers determined that vulnerable patients could not be discharged to homes without air conditioning; some patients will be discharged to a local arena, which was converted into a 250-bed facility.

Health centers, public health officials, and community leaders need to prepare for more Beryl-like hurricanes – earlier, stronger, and with less time for preparation. From Hurricane Maria to Hurricane Ian and now to Hurricane Beryl, we are receiving warning signs – but how do we prepare? Here, we present several practical considerations to mobilize and prepare migrant and immigrant communities for the climate-pressurized reality that we now face.

- Health centers need to develop community mobilization plans with deep involvement of the community to identify segments of the community who are vulnerable during a storm (like those with chronic illnesses who require electricity for refrigeration of medication or for medical equipment) or become vulnerable because of a storm (like farmworkers living in rural areas with limited communications, poor transportation links, and vulnerable infrastructure).

a) Understand the seven key elements of MCN’s Community Mobilization efforts for communities after disasters, and access numerous helpful resources, in “How Health Centers Can Work with Their Communities, Before, During, and After a Disaster,” from Streamline, MCN’s in-print quarterly clinical publication.

b) Use MCN’s communications manual, called “Designing Community-Based Communications Campaigns.” This 58-page manual, which is also available in Spanish, goes in depth into many parts of building a climate emergency plan and how to communicate the strategies. While the manual was initially built for a COVID campaign, the strategies and tactics are generalized for use in many campaigns, including for a climate emergency.

c) Groups like Direct Relief are helping health centers build solar-powered backup battery sources for long-term, climate-friendly energy in the case of longer-term energy disruption.

- Provide education and resources to patients who are newly diagnosed with a condition on what they need to do in an emergency given their condition, from accessing the correct foods and clean water, to continuing their treatment.

a) Read MCN’s Streamline article on Diabetes and Disasters as an example, with tips on nutrition, treatment and medicines, home monitoring and clinical concerns, and mental health and wellness.

b) Not all communities are equally at risk of poor outcomes during a service disruption. Because of the numerous barriers to health care, coupled with inconsistent access to the vital conditions for health like safe housing and workplaces, migrants and immigrants are at high risk of negative health outcomes during a climate emergency. These segments of the community require specific plans of action to prepare for disruption of service, even if people in those communities are considered “healthy” and without chronic disease at the time of disaster.

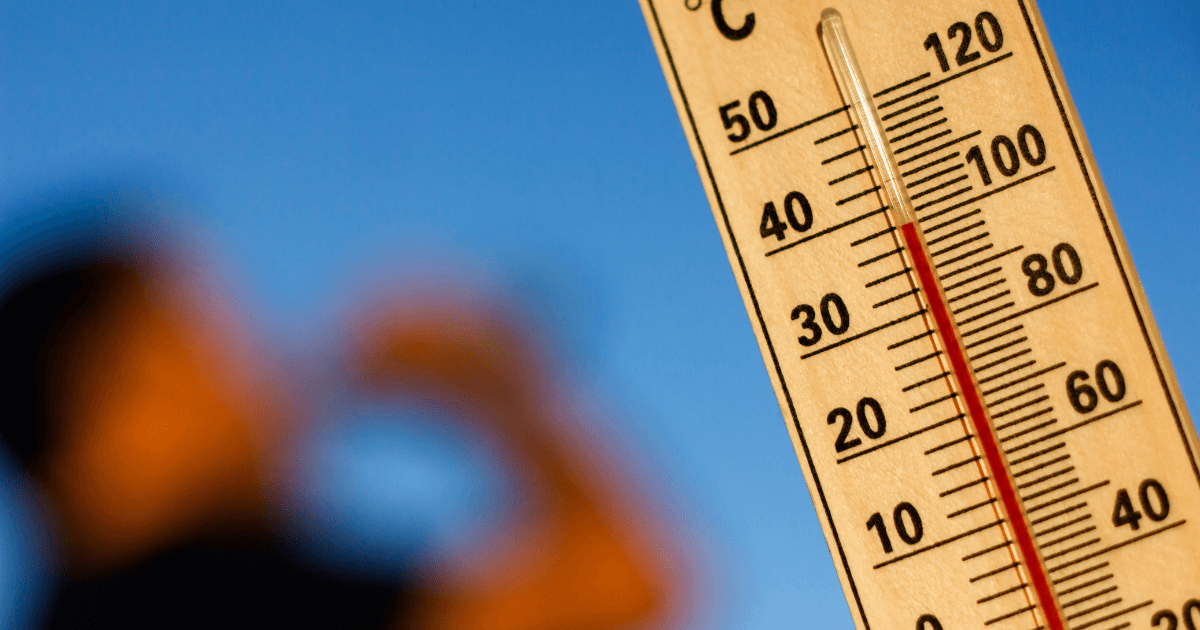

- Prioritize heat education, resources, and emergency plans -- year-round. Earlier and later heat, along with longer heat waves, have made heat preparation an emergency across the country and outside of the typical season in many parts of the country.

a) Engage Community Health Workers/promotores to effectively connect with the larger community.

b) Access numerous heat tools, resources, and archived webinars on Migrant Clinicians Network’s heat page.

c) Consider the needs of the health center and community when heat overlaps with other disasters like wildfire smoke and/or evacuations, and hurricane disruptions and displacements.

- Prepare for displacement. After Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, a health center thousands of miles away in Massachusetts received a large influx of new patients who fled Puerto Rico without their medications. Medical records were unavailable, as the island remained without power for weeks. Health centers who do not expect to be affected by hurricanes still need to account for influx of patients when a disaster strikes nearby, or strikes a region that shares a community with the health center’s patient population.

a) Learn about different types of climate migrants and their health needs in our recent peer-reviewed journal article, “The Climate Migrant: Health Risks Before, During, and After Migration.”

- Prepare for clean-up and demolition. Migrants arrive after a disaster to assist with clean-up and demolition. Even longtime workers in this industry who have inconsistent work will need to acclimate to heat, regardless of expertise, after a break in exertion during heat. And as Beryl demonstrated, workers who may have years of experience and may be already acclimated are still at risk when encountering unprecedented heat. Health centers need to be prepared to serve an entirely new temporary workforce with its own unique needs.

a) Learn more about climate-disaster workers and their needs. Equipping Climate Workers to Stay Safe: Health and Safety Training with MCN and Resilience Force

b) Resilience Force is a good resource for information and support.

- Log in to post comments