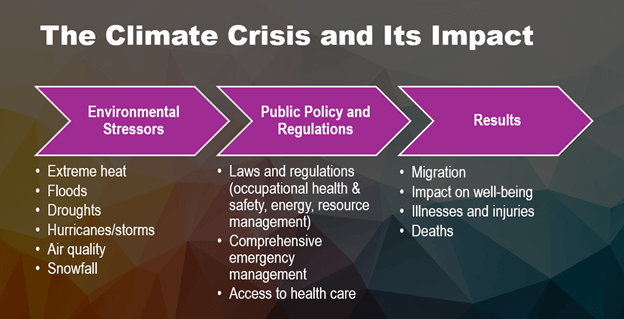

Community health centers across the United States and US territories are facing new, unprecedented climate emergencies that are greatly impacting their marginalized communities and their ability to serve those communities – even when those climate disasters may be happening hundreds or thousands of miles away. “The climate crisis is presenting emergencies that aren’t just new – they are harder to prepare for,” explained Marysel Pagán Santana, DrPH, MS, Director of Environmental and Occupational Health and Senior Program Manager for Puerto Rico at Migrant Clinicians Network. “And it isn’t just that communities haven’t had such a variation before. It’s also that emergencies are happening in communities where they never happened before,” and far-off emergencies can impact local communities, Dr. Pagán Santana added.

The fires across Canada in the summer and fall of 2023 provide an example. On June 1, a lightning event ignited over 120 fires in southern Quebec alone. The start of the fires coincided with the warmest May-June period in over 80 years, and an unusually dry season in the province, both of which dried out vegetation, allowing the fires to spread quickly.1 An analysis by research scientists with Natural Resources Canada, the department of the Canadian government responsible for natural resources like forests, found that “climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Quebec” last year.2 Throughout the summer and into the fall, as the fires continued, winds carried heavy smoke across international borders, leading to consecutive poor-air-quality days, thousands of miles away from the fires. In early October, for example, air quality dipped into “unhealthy” air quality levels across Florida.3 By the end of the year, fires had covered about 18.5 million hectares – roughly the same as the entire land area of North Dakota.

Across 6000 emergency departments in the US, visits for asthma were 17% higher than expected during days of unhealthy air from the Canadian fires, according to studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 Emergency departments in areas that have never experienced a wildfire – agricultural and urban areas without forests to burn, for example – experienced the health consequences of the fire. The CDC study concluded, “The risk of wildfire smoke exposure is increasing because of climate change, land management practice, and growth of wildland-urban interface areas, particularly in locations that have not historically experienced wildfire smoke,” and recommended that clinicians counsel patients on protective measures like staying indoors and using air filtration.

Yet, many marginalized patients, like migrant agricultural workers who worked through the smoke that blanketed large swaths of the US, are at high risk and are unable to take such precautions. (See text box.)

Why Are Agricultural Workers at High Risk of Wildfire Smoke?In this article, the 2023 Canadian wildfires are given as an example of an unexpected climate-fueled disaster that influences the health of people hundreds and thousands of miles away. The health effects of the disaster are not evenly distributed. Agricultural workers are at a greater risk of negative health consequences from wildfire smoke. Of course, their strenuous work outdoors results in greater exposure to the smoke. However, several overlapping factors further jeopardize their health during a smoke event:

|

Community health centers must prepare for a range of climate disasters that may impact their communities, even disasters/events that are thousands of miles away. Smoke isn’t the only traveler during a disaster; in some cases, community health centers must prepare for an influx of new patients escaping a climate disaster, like floods, hurricanes, droughts, and extreme heat. Given the wide range of scenarios, how can a community health center prepare?

In a recent Migrant Clinicians Network webinar, Dr. Pagán Santana and Alma Galván, MHC, Director of Community Engagement and Worker Training for MCN, provided practical approaches for preparation centered on the importance of understanding and engaging with the community. The webinar, presented in Spanish with simultaneous translation into English, focused heavily on community mobilization.

|

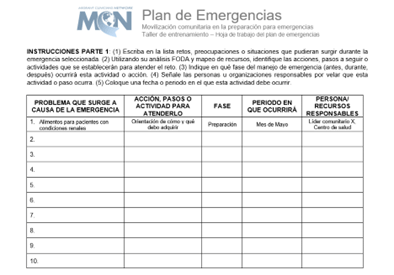

| Using this sample worksheet, a community in Puerto Rico with their local community health center to build a hyperlocal emergency plan with community buy-in. The instructions on the top: ask the participants to write challenges, concerns, or situations that may arise during the emergency; use their SWOT analysis and resource mapping to identify actions, next steps, or activities to address the challenges; indicate when the activity will occur (before, during, or after the emergency); and select a specific date or date range during which the activity will occur. |

“The fundamental principle of community mobilization is to ensure positive and sustainable behaviors among members of a community, where people are the ones who make the decisions and can take actions that benefit them,” Galván noted. Instead of instructing people on what they need or what they should do, community mobilization approach is participatory at its heart, Galván added, centering itself on inviting community partners and community members to share what they need and supports the community to organize itself and develop plans.

And it’s effective, Galván says. “It’s a proven strategy, used across Latin America,” she emphasized. Community health centers are already mandated to maintain an emergency plan; to make the emergency plan more effective, particularly for populations like agricultural workers who are frequently marginalized and underserved, health centers can employ community mobilization.

Galván delineated seven key elements of effective community mobilization, which can prepare a community and its health center for a climate disaster. “These are the pieces to glue the community aspect in with the health care aspect,” she said. “You can take this approach as one effective tool to tackle any public health problem,” including challenges beyond climate, in situations where health inequity needs to be addressed – from educational efforts on infectious diseases like COVID-19, to addressing food insecurity. Here, we outline these steps with climate in mind.

- Situation analysis: This is particularly critical when assessing climate impacts because the community may face climate impacts they have never experienced. Here, the health center identifies the potential risk the community may face as well as the possible impacts of emergency situations. Three types of impacts should be analyzed:

a) Direct weather impacts: Is the community at an increased risk of a heat event, flooding event, storm event? Consult climate scientists to determine what weather changes the community may experience. Online toolkits and databanks like climatecheck.com and riskfactor.com provide ratings for individual properties. Climate Mapping for Resilience and Adaptation, a part of the US Global Change Research Program, is a powerful tool that allows users to choose current or future community threats, at https://resilience.climate.gov/. Climate risks by county are also outlined at https://www.americancommunities.org/mapping-climate-risks-by-county-and-community/.

b) Indirect weather impacts: As in the case of the Canadian wildfires, what are the health effects on the community if another community experiences a disaster? In the case of a significant snowstorm or wildfire in nearby mountains, for example, what will happen to the community if mountain roads are blocked for months at a time?

c) Migration impacts: Health centers should consider their immigrant patient populations and the possibility of climate impacts in those origin countries. After Hurricane Maria, for example, a community health center in Massachusetts with a large Puerto Rican population experienced an unprecedented influx of migrants from the island, who arrived without medication and whose health records were inaccessible due to large-scale and long-lasting blackouts on the island.10

Galván recommends several strategies to better understand the community and the risks that they face. A SWOT analysis – in which “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats” are outlined – can be completed to assess how the health center is prepared or unprepared to advance the goals of the project. With the community, the health center can complete a KAP survey to determine the “Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices” prevalent in the communities served. Also with the community, the health center can complete a rapid needs assessment. Both the SWOT analysis and the needs assessment are outlined in MCN’s Communications Manual, which offers explanations and templates of these activities.

- Community resource mapping: To map resources, the community and health center partner to identify all the resources, overt or not. A community forum can be a good starting point for mapping the community, which in turn will inform the strategy in the case of an emergency. Resource mapping is also outlined extensively in the Communications Manual.

- Strategic planning: Together, the emergency plan can be built of shared decisions based on the data gathered in situation analysis and resources available. Participatory planning means that the health center is not building the plan; rather, many members of the community including the health center have come together, laid out what is possible, and made a plan jointly.

- Communication: Once the plan has been made, it needs to be well communicated so that, when activation needs to occur, everyone in the community knows what to do. What are the key messages for the community with which the health center wishes to communicate? Building a communication plan is not just what you will inform about, but how – where should people go in an emergency, what if they need help? “Have a clear plan of what to do, who is doing it, and how to effectively communicate, as well as having a spokesperson,” Galván added.

- Process of Health Communication: In addition to communicating the plan itself, the health center needs to communicate the steps the community might need to take in the case of specific health threats related to a climate emergency.

- Community implementation: Partners in the process along with the community activate the plan when an emergency occurs. It may be easy for a community member to get far along in the planning process, but not know where to start once a flood or a wildfire hits. This step is a reminder to complete the process and make sure that every step is actionable, so that when an emergency takes place, the next steps are ready to go.

- Documentation, Monitoring and Evaluation: “This is often misunderstood. It isn’t something to be done after the fact – it should be there throughout the entire process,” of building a climate emergency plan, Galván noted. “Community forums, for example, are a participatory way to get a sense of what is functioning and what is not,” a way for the organizers from the health center and community to gather opinions and assess their work while they are building the plan. Of course, after a climate emergency, and some time has passed from when a plan is initiated, organizers should once again come together, with strategies like the community forum, to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness and where it can be improved.

“It’s a beautiful process,” Galván concluded. “You will see it working – and it’s amazing. The community can do whatever they need to do to stay safe in a climate emergency. They just need the means and empowerment to do it.”

Watch the webinar, now archived on the Migrant Clinicians Network website, in English or Spanish: https://www.migrantclinician.org/webinars/archive. MCN’s webinars are free, most are available in English or Spanish with simultaneous interpretation, and many offer continuing education credits for those who attend live. Visit our Upcoming Webinar page: https://www.migrantclinician.org/webinars/upcoming.

Access MCN’s communications manual, called “Designing Community-Based Communications Campaigns.” This 58-page manual, which is also available in Spanish, goes in depth into many parts of building a climate emergency plan and how to communicate the strategies. While the manual was initially built for a COVID campaign, the strategies and tactics are generalized for use in many campaigns, including for a climate emergency. https://www.migrantclinician.org/resource/designing-community-based-communication-campaigns-manual.html

Explore national community mobilization efforts in Latin America for other health risks. All of these resources are in Spanish.

- Learn about El Salvador’s strategic plan for TB: https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2023/10/1512604/plannacionaldeabogaciacomunicacionymovilizacionsocialparaelcon_6rDSlXr.pdf

- See how Honduras uses community mobilization against COVID:

https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/2-3-2020-alianzas-movilizacion-comunitaria-para-enfrentar-covid-19

- Access a step-by-step guide on risk communication and community engagement on the Zika virus. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/33671

- Read about Dominican Republic’s National Strategy. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/31104

References

1 Webber T. Climate change doubled chance of weather conditions that led to record Quebec fires, researchers say. Associated Press. 23 August 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://apnews.com/article/canada-wildfires-climate-change-analysis-38a64e59ff5b73fcdeadb8fb90ccb073

2 Canada’s record-breaking wildfires in 2023: A fiery wake-up call. Government of Canada. 8 September 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/simply-science/canadas-record-breaking-wildfires-2023-fiery-wake-call/25303

3 Speck E. Canadian wildfire smoke invades Florida choking skies with smoke, unhealthy air quality. Fox Weather. 4 October 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://www.foxweather.com/weather-news/florida-air-quality-canadian-wildfire-smoke

4 Asthma-Associated Emergency Department Visits During the Canadian Wildfire Smoke Episodes — United States, April– August 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 25 August 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7234a5.htm

5 Seda C. Overlapping Environmental Factors, Paired with Social Determinants like Diet and Stress, Set Up Agricultural Workers for Poor Respiratory Health – And A Whole Host of Other Health Concerns. Streamline. Migrant Clinicians Network. Spring 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://www.migrantclinician.org/streamline/2023/spring

6 Bethuel NW, Wasson K, Scribani M, Krupa N, Jenkins P, May JJ. Respiratory Disease in Migrant Farmworkers. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(8):708-712. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000002234

7 Clarke K, Manrique A, Sabo-Attwood T, Coker ES. A Narrative Review of Occupational Air Pollution and Respiratory Health in Farmworkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4097. Published 2021 Apr 13. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084097

8 Seda C. Overlapping Environmental Factors, Paired with Social Determinants like Diet and Stress, Set Up Agricultural Workers for Poor Respiratory Health – And A Whole Host of Other Health Concerns. Streamline. Migrant Clinicians Network. Spring 2023. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://www.migrantclinician.org/streamline/2023/spring

9 Pagán-Santana M, Liebman AK, Seda CH. Deepening the Divide: Health Inequities and Climate Change among Farmworkers. J Agromedicine. 2023;28(1):57-60. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2148034

10 Seda C. Pharmacists Play a Key Role in Care Team at Holyoke Health Center. Streamline. Migrant Clinicians Network. Winter 2023/2024. Accessed 2 May 2024. https://www.migrantclinician.org/streamline/pharmacists-play-key-role-care-team-holyoke-health-center