COVID-19 has dramatically and repeatedly altered the daily lives of health care workers, and a day in a clinic or hospital today is not the same as it was a year ago when vaccines were first introduced. In this interview, MCN’s Claire Hutkins Seda, Senior Writer and Editor, sits down virtually with Kaethe Weingarten, PhD, MCN’s Director of the Witness to Witness program to better understand the landscape of moral injury among health care workers in recent months, and strategies to alleviate or comfort clinicians and patients as the health care setting remains overwhelmed and full of conflicting pressures. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

CS: We're entering year three of COVID in the US. What are you seeing now among health care workers, that is different than, say, six months or a year ago?

KW: From our vantage point, there are significant differences, and the Witness to Witness program is really trying to reflect back, in an accurate and empathic way, what we're seeing.

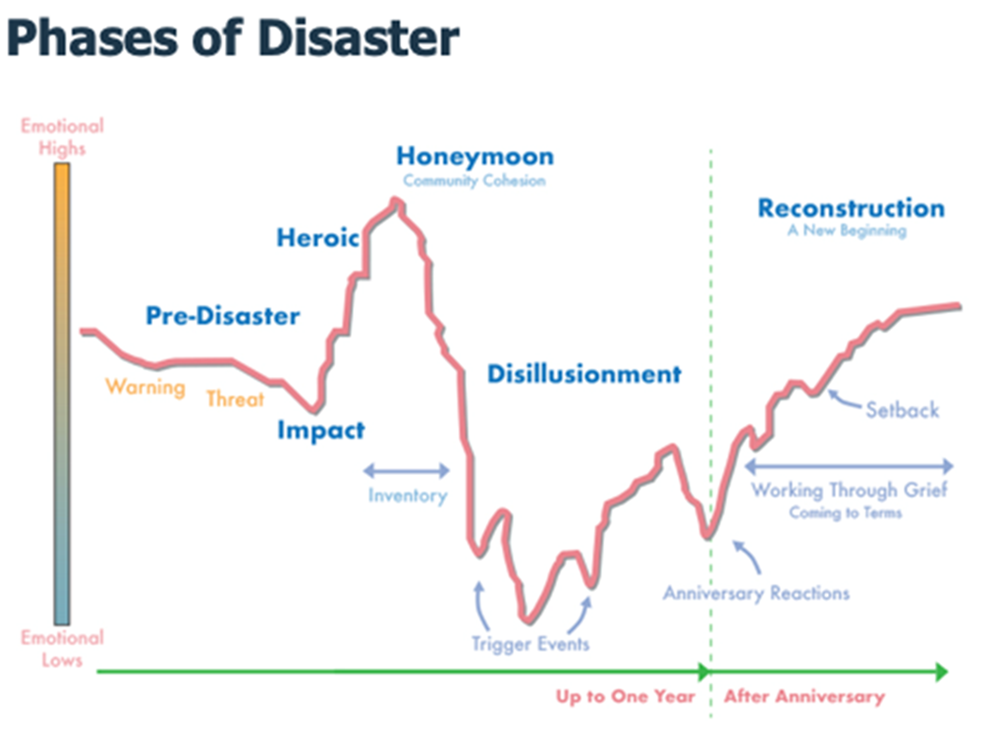

There's a visual graph that I've been using at the beginning of many of the online seminars that W2W does. [See graph below.] We've been using it for about a year, and it charts what happens in a disaster in terms of the community’s response.

Source: Homeland Security Digital Library, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=4017

[First,] there's a heroic phase. Health care workers will remember what it was like in the first few weeks, when they were treated as heroes. Then, the honeymoon phase -- and it's actually called that, the honeymoon phase – ended, and there was a downward slope, you can see it in the way the graph is drawn. It begins to pick up again at about the one-year mark, and it enters what's considered to be a recovery or recuperation phase. I think we thought, in the beginning of last year, in January [2021] when vaccines became available, that that was going to be the scenario. And I think that many health care workers had an expectation that things were going to get better. They were going to be less stressed. People would come together, vaccinate for the good of the community even if they were hesitant, and that herd immunity would happen -- and that scenario, for the most part, has not come to pass.

What we are now seeing is that health care workers are clearly overwhelmed. They are no longer being treated as heroes. They are on the receiving end of many different kinds of abuse: verbal abuse, physical abuse, threats. And it is taking a toll in many ways, including that we now have one of the highest attrition rates that the health care workforce has ever experienced. The survey data for nurses shows that a majority of nurses are contemplating either leaving their jobs or leaving the profession in the next year.[1][2][3] They are also dealing with greater frequencies of microaggressions, both from colleagues and patients. The term ‘micro’ doesn’t mean that the interaction is minor; it means that it is a daily occurrence. When people are worn out and exhausted, all kinds of hurtful comments can be thoughtlessly made.

CS: That rate of contemplating leaving the profession, that’s incredibly high, more than 50%. Has this happened before, to this level?

KW: There's no precedent. So, what is the day-in and day-out experience of a health care worker like, and how is it different from a year ago? A year ago, people were stressed, they were overwhelmed, they were dealing with shortages of PPE, they were dealing with moral injury. And they were having to make choices, essentially triage who was going to get what level of care, and that violated people's principles, but they were not angry, they were not feeling abused. They were not worried about being attacked, they were not worried about their own physical safety or the safety of their family member from others. The safety issue they contended with was from a virus, not a person.

Now what we are seeing is that all of those factors are still present, but people are in a very particular quandary: they're working with people who continue to deny that COVID exists. They’re intubating people who are perhaps going to die and who are saying, ‘vaccinate me now.’ People who are unvaccinated and hospitalized are taking beds from people who have gotten vaccines on time, but had other medical or surgical issues and they now can no longer be hospitalized. Doctors and nurses are no longer working on units in the area they were trained for; they are working in COVID ICUs.

I heard an anecdote over the weekend about a 75-year-old who's been walking around with a painful hernia for three months. He cannot get a bed to have the procedure because there's no room and no surgeon available.

People of all ages are not able to access medical care and the health care workers are in the position of telling people, ‘no, we can't serve you’ or, ‘it's going to be six months before you can see somebody.’

[And there are other types of shortages as well.] The surgeon general, as you probably know, declared a pediatric mental health emergency. The ratio of mental health providers to the population that needs [mental health care] is completely out of whack.

Health care workers are suffering because they're trying to provide adequate health care within a system that cannot stretch to do it. So then what do they do? Do they become part of the problem, or do they say at a certain point, ‘I have to take care of myself and I can't participate in a system that's broken, and I can't allow myself to be broken?’ It's a very different situation than what we were looking at, really, even nine months ago. In some states, they have called in the National Guard to help communities with massive shortages.

CS: You mentioned briefly moral injury. Can you describe what you mean by that, and how it's changed over time?

KW: Yes. In the 1980s, there was a term ‘moral distress.’ It was developed in the nursing literature, and it was specifically talking about the experience of a nurse who had to follow through on an order from a physician or a surgeon that he or she didn't believe was the correct order.

In a completely other context, of returning veterans from the Vietnam War, in the early 1990s, Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist, developed the idea of moral injury as a category distinct from, and with a different symptom picture from, post-traumatic stress disorder. He noted that when returning veterans talked about some of their experiences, they spoke about obeying orders that violated their moral code. And when they did so, they felt betrayed by either their unit commander or the overall strategy of the war itself.

The term “moral injury” made clear that what had been violated was the returning soldiers’ moral code or moral values, and it turned out that there was quite a different kind of treatment that was necessary to heal or, better, comfort people or validate their experiences.

In the context of health care, I think there's always been both moral distress and moral injury. It's just that before COVID, while an experience like that might have occurred once a week, now it might be happening every few minutes, and it's almost impossible for people to stay present and process, one, the frequency with which moral dilemmas arise, and two, the intensity.

So, just to give you an example I've heard over and over again from health care workers: [health care providers are having to] present a phone or an iPad to somebody who is dying [of COVID in the hospital in isolation] and being the intermediary between them and their loved ones. There’s a two-minute window when the patient and loved ones can say goodbye. This is so profoundly in violation of what any caring person wants to provide [during] the transition into dying and death.

CS: It seems there are two ways to address the witnessing of these traumatic events. There are systems that need to be altered, and there are individuals’ responses. Let's start with this systems-level. What needs to happen?

KW: At a systems level, I think that one of the primary actions that leadership -- from the CEO all the way down to the unit manager -- can take is to acknowledge that this is happening. The very act of saying, ‘we know this is so, and we have tremendous gratitude for the work that you are doing. We are incredibly appreciative. We know it's extremely difficult.’ That's one piece that leadership can do.

Second, I think it's really important -- and this is something that I've built into all of the [W2W] work, [including online] groups and seminars -- to be clear that burnout is not the best term for what people are experiencing. So again, at the level of leadership, noting that moral injury is very different from burnout, that burnout has an unfortunate implication that an individual is inadequate in some way, is lacking some internal resource which, if they had that resource, they'd be fine.

[Third,] to have leadership acknowledge that burnout is a consequence of failures of the work situation itself. It's a transform of problems in the workplace. Ninety percent of burnout is about conditions in the workplace that are experienced by individuals. What we are experiencing is mostly not burnout.

On the individual level, what are the daily actions that we can take to cope with moral injury? The frames that I'm using are several.

One is that people really need to remind themselves on a regular basis that it's the systems that are producing circumstances that create harm -- it's not individuals. There's no intention to harm.

Two, if possible, people [can develop] a buddy system so that during the workday, they're able to quickly debrief with somebody so that they're not putting every episode in their emotional ‘backpack,’ and by the end of the shift, it’s 100 pounds…

Third -- you can see that I'm contextualizing what individuals can do when working with colleagues – so, at the end of the shift if possible, or at the end of a workday, [work colleagues can] offer acknowledgement and appreciation, just do a little huddle. It doesn't have to take more than two minutes. It's doesn’t need to take a lot of time, but if I call out somebody and say, ‘I really appreciated when you did this,’ and there's that kind of acknowledgement that happens, it really does help.

Then, of course, there are many biological or physiological re-regulating practices that we do, including just managing the breath by [doing] simple breathing exercises.

CS: So we've been talking specifically about what health care providers can do for themselves, but then they also have the responsibility of taking care of their patients who are changing as well as a result of the pandemic, for example, you mentioned the mental health crisis among children. So are there some strategies that clinicians can employ or innovate in their work to keep up with these changing times?

KW: I think I'm leaning on two ideas. The first being acknowledgement and the second, that clinicians are in fact witnesses. They're actors, but they're also witnesses. And to have somebody listening compassionately to your experience and having some verbal exchange about it as the actual provision of medical care is happening makes an enormous difference for people.

[Individuals] can tolerate an enormous amount of distress if it's in connection. Health care workers are in a prime location to offer that kind of connection. And two things we say over and over again: One, this does not take time. The acknowledgement and attuned listening and reflecting back to a patient can take one minute.

Second, it's really important for health care workers to understand that something, a gesture that they do that maybe in the big picture [seems] small, is radically different from it being trivial. Small things that we do matter. It's important to realize that you never know what the ripple effects out are going to be.

CS: A lot of Streamline readers are at health centers that specifically serve historically marginalized populations including migrant agricultural workers. As you know, many people have compounding barriers to accessing health care and some put aside their health while they are migrating, or the health provider may only see them once as they are moving and not see them again. Are there any other comments that you want to add, specifically for clinicians serving those type of communities?

KW: I think anytime a clinician is in that circumstance, offering appreciation and praise for the person having gotten themselves to a health care center is a number one priority. You don't know what the obstacles were in the way of the individual showing up, so acknowledging that, likely, there were many obstacles and appreciating the person that they arrived, that they were attending to their well-being -- I think that is a key step in the clinical encounter.

Resources:

Dr. Weingarten has developed, and continues to develop, numerous resources, most available in English and Spanish, for health care providers. Three of these resources, on moral injury, anger, and restoration of equanimity, are included in the following pages. Download these and many other resources at: https://bit.ly/3IYbpLg

Visit the Witness to Witness webpage to learn more about peer groups and online seminars: https://www.migrantclinician.org/witness-to-witness

Visit our Archived Trainings page to watch recent webinars that you may have missed: https://www.migrantclinician.org/archived-webinars.html

Dr. Weingarten publishes one blog post each month discussing topical mental health concerns and W2W strategies, on Clinician to Clinician, MCN’s active blog: http://www.migrantclinician.org/blog

1 https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2589-5370%2821%2900159-0

2 https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Clinician-Burnout-Infographic_FINAL_print.pdf

3 https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aa484/globalassets/docs/ancc/magnet/mh3-written-report-final.pdf

Read this article in the Winter 2022 issue of Streamline here!

Sign up for our eNewsletter to receive bimonthly news from MCN, including announcements of the next Streamline.