In the northern end of the Sacramento Valley of California, the world’s biggest struggles and tragedies are played out in rural agricultural neighborhoods, and in the lives of everyday people. By the end of August 2021, a climate-strengthened drought complicated by growing populations and agricultural water mismanagement had impacted groundwater levels and dried out forests. Many people who rely on wells for drinking water found their wells mostly dry, the water coming out their pipes gritty with sediment. Meanwhile, skies were once again blotted out with smoke, as wildfires raged in the foothills just beyond the valley, a scene that has become almost an annual event. A low uptake of vaccines in the region caused local rural hospitals to once again fill up with COVID-19 patients, a deadly spike that would last through September.

These overwhelming tragedies slowed down, but did not overtake, Robin (Robyne) Hayes, a photographer who specializes in storytelling and the concept of photovoice, giving voice to marginalized peoples’ stories through their photography. For two years, Hayes had been coordinating with Jillian Hopewell, MPA, Migrant Clinicians Network’s Director of Communication and Education, to launch Tu voz importa, a photovoice project in which Latina immigrants and Latinx youth from northern Sacramento Valley could reflect on their lives and their communities through photography, sharing insights with the larger community. “There are so many negative ideas around immigrants,” and so one of the primary goals was to “show we’re all similar, regardless of where we come from,” Hayes noted. “But also, it’s important that people see their own stories reflected in the stories in general. The fact that we’re hearing from immigrant women, I hope that other immigrants see themselves in this, and realize their stories are powerful and important, too.”

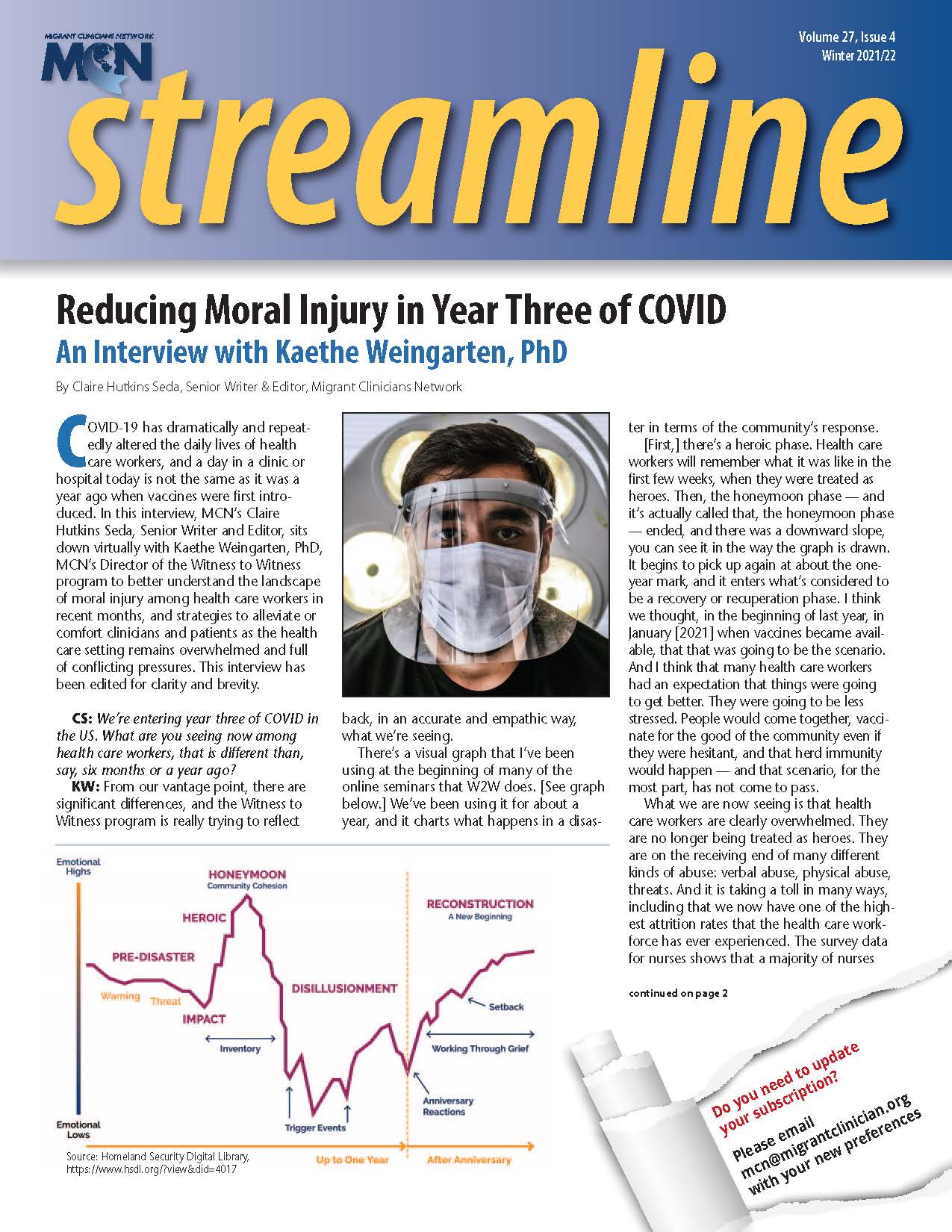

Fires in 2020 and ongoing COVID infections had already forced the cancellation of the start of in-person workshops in fall 2020. In June 2021, two groups finally began the long-delayed bimonthly in-person sessions. During the first class, participants received cameras and training on how to use them. They also covered issues like photo consent and how to take anonymous photographs. Then, classes shifted to more creative assignments for participants to explore their notions of family, self, and community. Las Promotoras, health promoters with Northern Valley Catholic Social Services, coordinated the participation of nine immigrant women participants, most of whom work at a local cannery, and five Latino youth, ages 13 to 15. The local county’s Office of Migrant Education recruited two additional groups, coordinated as part of two summer school English writing classes, that met on Zoom. Cameras were donated or borrowed, and in-person class participants also received a meal at every class, generously donated by local businesses. The most important aspect of the workshops is the discussions. In between workshops, participants take photos of their lives and their stories, and then return to the group to discuss their favorites. The in-person classes got off to a good start, but midway through the summer, Hayes noted the women participants flagging a little. “I think they didn’t know exactly where it was going,” she said, noting that “they have a lot of hours at work, and a lot of responsibilities.” They also hesitated on some of the assignments. A request for self-portraits was not fulfilled by many of the participants, for example. Hayes suspects that this is partly due to how much time and effort they spend working for others, at work and at home, and partly a reflection of their culture, which is not as centered on the self as “individualistic America,” she said. “But at the end, they all enjoyed coming, they all stayed longer [after class], and they had fun.”

The youth groups varied in engagement. The in-person group thrived. In sharing their perspectives through photos and conversation, “I think they didn’t realize that everyone has the same thoughts” as they do, and enjoyed finding others who share similar struggles, Hayes noted. “It made them feel less alone.”

Fifteen-year-old Gabby Lacy agreed. Lacy, as the daughter of a promotora who helped coordinate the workshops, did not necessarily volunteer to join the group. “My mom wanted me to do it. I was okay with it – I didn’t really mind,” she admitted. At first she was nervous, as the youth came from across the northern Sacramento Valley and she didn’t know any participants, except her sister. Soon, however, the class coalesced around the topics Hayes presented, that the young participants explored through photography. During the workshops, they found common ground. She recalled a fellow participant’s photos of family members, and her contextualization about the difficulties and joys of caring for and spending time with extended family members. “I really understood that. Even though I’m the youngest [in my immediate family], I have little cousins, and I understood her struggle – how crazy they could get, or annoying. But then, they can also be cute and friendly-ish.”

One of Lacy’s favorite photos generated during the workshop is a self-portrait where she set up the camera and jumped over it, producing a “cool effect with the sun,” she said. In addition to the photography skills she gained, however, she says the group also learned about their communities. The project “really put our lives in a perspective, of how we can affect the community,” she said. It also spawned conversations around needs in the community, including around growing homelessness in the region.

The online groups were more difficult to assess. Those classes were comprised of migrant students, many making up high school English credits as a result of school interruption as their families moved for work. The classes ran into many of the same issues that online schooling has faced throughout the pandemic, including internet bandwidth, no space in the home for private calls, and a lack of engagement due to discomfort and distraction. The Zoom-based students rarely shared photographs or participated in discussions. “As with so many low-income students, the many challenges they faced with COVID, Zoom courses were not a good solution, but there was no opportunity to hold classes in person,” Hayes said. The groups finished out the project as part of their coursework, but did not prepare photos to share in the group exhibits.

Then came August. In the final sessions, in-person participants were to select and caption their favorite photos, to be used in formal, public exhibits, as well as an exhibit and celebration for their family and friends. However, there was an outbreak of COVID-19 in the community and the wildfires were once again severe. Even outdoor classes were unsafe. The final classes had to be pushed back a month.

The pressing themes that define the times, and that interrupted the classes – disaster, isolation, destruction – were not the defining sentiments in the photos that participants took. The challenges of low-wage work or immigration were also absent. Instead, among the women, Hayes saw recurring themes of solace and rejuvenation found in nature, the importance of family, and remembrance of their homelands. “A lot of them were thinking about home – where they grew up, their families, life and death,” Hayes said.

For the youth, many reflected the challenges of sharing different faces at school and at home, about “feeling like they have to present themselves in a certain way, and live up to gendered social expectations in school, but feeling like a different, freer, and more genuine person at home,” Hayes said. “During this really hard age, they were able to have a space where they could talk and share and be empowered by their stories,” Hayes shared. “It sounds cliché, but it was really a space for them to have fun and make friends and realize they’re going through the same thing.” The youth group went further, moving their discussions into the realms of advocacy. “They wanted to address homelessness. They talked about vaccine hesitancy,” Hayes recalled.

Now that the classes are over, the next step is to develop the exhibits to share their work, which are slated for this spring. The posterboards with favorite pictures will be presented to family and friends during a private exhibition. Their favorite photos will be framed and mounted and accompanied by the stories the participants wrote in English and Spanish for a more formal public exhibit at California State University, Chico.

“The Tu Voz Importa photovoice project is an opportunity for the public to meet people in our community whose stories they may not know,” emphasized Heather McCafferty, Faculty Curator at the Valene L. Smith Museum of Anthropology, at California State University, Chico, where the formal exhibit is to be held in late February. “Your Voice Matters is the translated title, which conveys to participants that they belong to this community and empowers them to tell their stories through photography, a medium capable of capturing the ordinary and extraordinary of daily lives. The museum hopes to provide a safe place for participants to share a glimpse into their lived experience - through the lens and through their captions printed in Spanish and English.”

“The important part of the process isn't just the photos, it’s their stories and captions as well,” Hayes emphasized. In the exhibits, “their photos and captions are woven together to create their personal narratives.” Hayes also hopes to provide smaller exhibits at more intimate settings where the photographers’ communities can easily enjoy them around Chico, like at local community housing. The efforts also are set to expand with a new grant from the CDC Foundation to work with local Latinx youth and adults to create a photographic representation of the impact of COVID on daily lives. The novice community photographers will then work with graphic designers to create educational materials to help combat vaccine hesitancy.

The following pages include a selection of the photographs and captions created during the photovoice project. See many of the photographs and their captions on MCN’s Instagram and Facebook accounts:

https://www.instagram.com/migrantcliniciansnetwork/

www.facebook.com/migrantclinician

Learn more about Robyne Hayes’ work at: https://www.robynehayes.com/

Learn more about MCN’s photovoice project at: https://www.migrantclinician.org/your-voice-matters

Read this article in the Winter 2022 issue of Streamline here!

Sign up for our eNewsletter to receive bimonthly news from MCN, including announcements of the next Streamline.