A patient’s medical history is rarely comprehensive enough to indicate the forces at play that cause vulnerabilities that lead to health problems. Instead, the clinician may only react to the circumstances presented in the exam room. To improve care for patients, remove barriers to care, and improve the patient-provider relationship, many efforts have been made to expand the lenses through which one views such an encounter; these efforts have led to the incorporation of frameworks of cultural humility and social determinants, for example. In a recent four-part webinar series on structural competency, Seth Holmes, PhD, MD, a physician and medical anthropologist at University of California, Berkeley, who authored the book on migrant health Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies; Deliana Garcia, MA, Chief Programs Officer of International and Emerging Issues with Migrant Clinicians Network; and Cheryl Seymour, MD, Professor in the Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency and with the Maine Migrant Health Program, encouraged participants to look beyond the charts, and even beyond the social determinants and health equity factors that initially led to the health challenges, to consider the structural forces at play that created those barriers.

“When I work with clinicians… I like to ask them to think of a particular patient -- someone with diabetes or a chronic condition -- and think through: why is that person sick? A lot of times the ideas that people come up with … are [related to] biology, behavior, or culture,” explained Dr. Seymour in the opening session of the series. “There’s another way to think about why people are sick. That is the idea of the social structures that influence a lot of other aspects of their daily lives.”

As an example, Dr. Seymour presented the case notes of a recent patient in Maine who attended a check-up at a community health center. The patient, a 66-year-old Haitian migrant farmworker, presented to the clinic with partially completed medical bottles labeled in English, a hemoglobin A1C of 12.6, and very high blood pressure. Because the measures for her previously diagnosed conditions were uncontrolled, she was marked on her chart as “non-adherent.”

In talking with the patient directly, Dr. Seymour found that she had immigrated to the US with temporary protection status (TPS) from Haiti after a natural disaster displaced her. Through friends, she found employment with a “crew boss” who contracts with East Coast farmers. This led her to move for work every two to three months across the entire Eastern seaboard. Because of her reliance on her employment, she was experiencing limited food choices, isolation, mobility, poverty, and little to no access to a kitchen. In examining her prescription, which was worn out (perhaps indicating that she had been traveling with it for some time) and which only had instructions in English, Dr. Seymour found that after her diagnosis with diabetes, she was provided with drug samples. Many of these factors contributed to the patient’s current health state, and her inability to address her diabetes and hypertension through diet, exercise, and medical compliance – and the recognition of these many factors is an important first step, but, Dr. Seymour argues, should not be the last step. “We stop at, ‘well, this is a Black person, or this is a farmworker, and they’re more likely to live in a densely populated area, they’re more likely to have less access’ – all of these [factors], we put in from the realm of a risk or characteristic of that individual. That’s great [that] people understand that – but there’s another ‘why’ that we’re not asking. Why are these people more likely to be in this situation?” This is where the structural framework comes in.

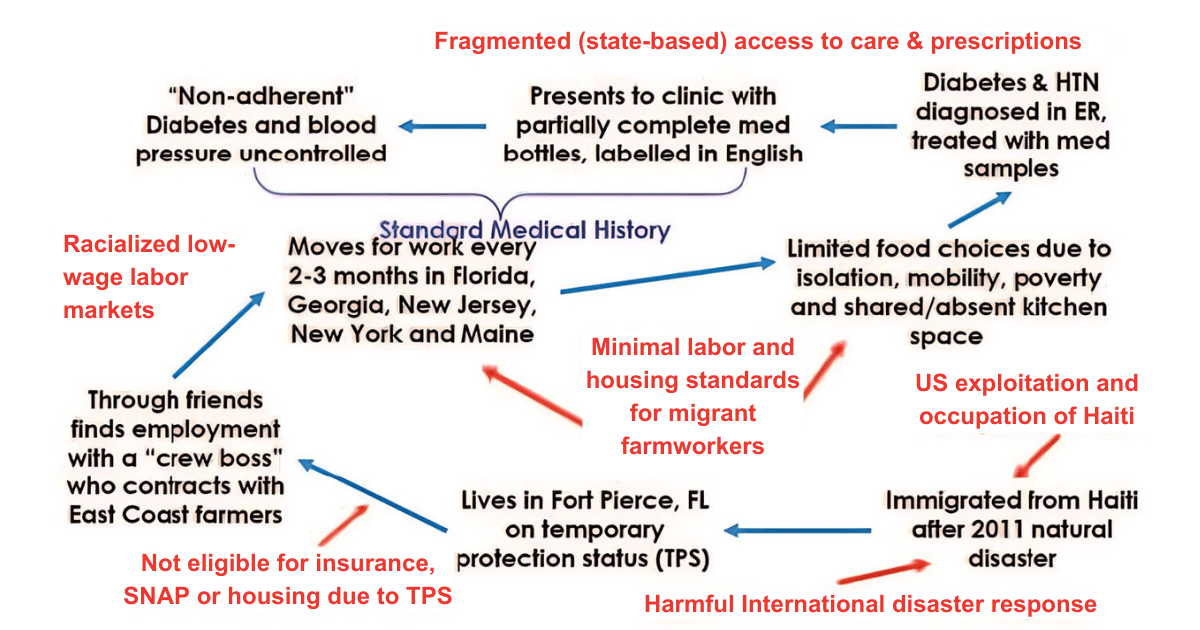

Taking a structural lens, Dr. Seymour further broke down this patient’s story using an arrow diagram to point out the structural forces like policies and health systems (in red) that contributed to the factors that led to the patient’s health conditions.

“These words in red are a way that we are presenting in a visual way to you the social structures that cause, or are related to, these elements that are part of this patient’s story,” said Dr. Seymour. “The premise, the idea that we’re trying to introduce… is that the US foreign policy relationship… those policies and decisions made at a very different level… than my patient in Maine, those decisions are directly impacting and relevant to her A1c of 12.6, as is the lack of labor and housing standards, the way that access to care is fragmented in our country, etc.”

These structural forces create the barriers that affect the health of patients. The screenings that are in place today at health centers name the social determinants of health – poverty, social isolation, lack of transportation, food deserts – that drive the health conditions of our patients. However, these screenings do not give clinicians a complete picture of what created the social determinants in the first place. To build a more comprehensive understanding of why a patient is ill, one must look outside of the individual’s experience, and into the larger social structures – policies and regulations, immigration practices, and health care systems – to identify root causes.

Of course, many of these root causes are not structures that clinicians in a health care setting can easily influence for better patient health outcomes. But building structural humility – the act of clinicians paying attention to the role of structures in patients’ lives, and working with patients with these structural forces in mind – is a key first step. “Being aware of these factors and encouraging clinicians to connect patients with important social work, community health, and other community resources can be important in preventing the clinician from blaming the patient's behavior, biology, or culture inappropriately,” added Dr. Holmes. “In other words, the structural lens helps clinicians avoid inappropriate etiological understandings and inappropriate recommendations.”

“Structural humility reminds us not to make assumptions about the role of structures in patients’ lives, but instead encourages us to collaborate with patients and communities in developing responses,” explained Dr. Holmes. By considering the structures at play, clinicians can alter their entire view of their patients and their patients’ needs. For example, health advocates often talk about agricultural workers as a “vulnerable population,” due to the many barriers to good health and quality health care that they encounter. But the individuals who make up an agricultural workforce are not inherently vulnerable – they are made vulnerable by the structures that they interact with in the course of their work. Therefore, an agricultural worker patient who is struggling with his health and is “noncompliant” is not just struggling because he’s an agricultural worker and it’s inevitable. He is experiencing and responding to structural forces that developed over time.

“This is meant to counter the usual way we think about it in health, and show us that [vulnerability] comes from structures that can be changed and can be resisted,” noted Dr. Holmes.

Implicit Frameworks

“If we are not thinking structurally, then we are thinking through another implicit framework,” added Dr. Seymour. Implicit frameworks are ways of thinking or lenses through which one looks at a patient’s situation that may be automatic, deeply ingrained in our processes and practices, or adapted through education and experience. Implicit frameworks that are common in medical practice include cultural, behavioral, and biological or genetic frameworks.

Cultural frameworks were built as a response to the understanding that many clinicians in the past, particularly white, male physicians, were making assumptions about their patients based on their own experiences, and making clinical decisions in an ethnocentric way. “Cultural competence reminds us that people have different experiences and backgrounds,” said Dr. Holmes, which is important and useful to ensure that different people’s experiences and lifestyles are recognized. “But sometimes, it ends up listing traits for ethnicities – which gives us a way to not have to explain” the issues that a patient is facing by instead chalking it up to their ethnicity. “It can be a shortcut so people don’t think of what else is going on,” he said.

Dr. Seymour again gave an example related to her Haitian agricultural worker patients. Taking a patient history from a person from Haiti “flows differently than other types of interactions I’ve had,” she said. This can lead a provider to conclude that getting a complete and chronological patient history from a Haitian patient will be very difficult or impossible, because Haitians “must not think of time the way that we do,” she said. “What is true is that, yes, of course, there are all kinds of things that are different from one culture to the next,” but when culture is singled out as the reason for the struggle, “we’re putting that on the patient, which then absolves me as an individual and also absolves the system from creating the place [and] an opportunity to actually communicate effectively. Rather than me figuring out another way to get the information I think I need to help them, I’m just like, ‘it’s going to be hard to get a timeline.’”

Behavioral frameworks are another way of thinking about a patient’s history that places the onus on the individual’s behavior to explain illness. “The patient is choosing to eat certain foods, or to not take their medication,” Dr. Holmes related. Another example is the agency with which people choose to migrate to the US to do farmwork. “People are choosing to come to this country – but there are forces that are informing [these choices].” While they may have made the choice to migrate, their options to stay in their home country may be limited or eliminated due to poverty, political instability, climate disasters, and other factors. These factors in turn may be resultant from geopolitical decisions and international policies from here in the US.

Biology and genetics are other frameworks that one must be wary not to lean on too heavily without considering the structural factors behind them. “Every time we talk about a health disparity, if we don’t include in that conversation some kind of structural acknowledgement, then [from] a statement that big – ‘Black patients have more severe hypertension, have higher mortality from cardiovascular disease, period,’ without that additional structural clarifier -- one might internalize the idea that Black people just have higher blood pressure, that there’s something about having black skin that makes you more likely to die, that it’s something about the biology or genetics of that person that is leading to that health disparity,” offered Dr. Seymour. “Whereas, if we pull back from that, we can name all these different social structures that have led to poor health status, for example, for Black Americans.”

But “we can’t just be focused on vulnerabilities and what is hampering the person. We need to consider the vital structures that must be in play so that the person can take full advantage of their opportunities,” adds Deliana Garcia, Chief Program Officer of International and Emerging Issues for MCN. “Everyone needs and deserves humane housing, health and safety, and meaningful work, and other structures that are vital for a thriving community.”

Clinicians’ Role in Structural Competency

Dr. Seymour acknowledges that building an arrow diagram of a case to identify the many causes of a patient’s health concerns and the structures that are imposing on those causes is not something that a clinician can do for each patient. “I would not have the information to do that – which is, kind of, one of the points. In the absence of having the context and the ability to do some structural analysis, we end up using other ways of thinking and other lenses,” she noted. But building structural awareness is an important role that clinicians fill, “as important as actions at large levels to alter those structures. Both need to happen,” she added.

In order to think in structures, clinicians can gather information, find partners, work within the community, to determine what the community believes is important. The role of clinicians “is not to necessarily to have the answers; in fact, it’s usually not to have the answers,” Dr. Seymour explained. “What we do have is a great amount of power, and our ability to narrate that the cause of this problem is not going to be sufficiently addressed by [solutions like] a blueberry rake, or by a new access point – that there’s more that needs to be done, our ability to say that, in the forums that we have, is important.”

All three presenters are active in the Structural Competency Working Group (www.structcomp.org), which has developed a set of screening questions to help clinicians uncover and understand structural vulnerabilities. “The attribution, the causality of the harm, is still not, ‘this patient is food insecure.’ Yes, we should get them food – but it continues to point to the fact that food insecurity has a structural cause, which can be ameliorated. Maybe not now, but we can’t lose track of that while we’re meeting the immediate social needs,” said Dr. Holmes. (See sidebar for example questions from the screening.)

A Structural View of Clinical Care

This structural approach can be taken to review a clinician’s own experiences in health care provision and the barriers they face within their health center.

“We saw during COVID that clinicians came up against a number of structural barriers that they could not affect – limited PPE, insufficient staff, historic number of deaths, and no reliable treatment or prevention,” said Garcia. “It was chalked up to burn out, but we know that these were insurmountable structural barriers that clinicians confronted daily, and their spirits took a beating. We know that this results in moral injury because the outcome violated their values and professional commitment.”

Structural Vulnerability Assessment ToolIn a journal article entitled “Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care” in Academic Medicine, Dr. Holmes with Philippe Bourgois PhD, Kim Sue MD, PhD, and James Quesada PhD published an assessment tool to “highlight the pathways through which specific local hierarchies and broader sets of power relationships exacerbate individual patients’ health problems is presented to help clinicians identify patients likely to benefit from additional multidisciplinary health and social services.” Here, we excerpt one list of screening and personal questions on discrimination. Discrimination[Ask the patient] Have you experienced discrimination?

[Ask yourself silently] May some service providers (including me) find it difficult to work with this patient?

Access the entire article which includes other screening questions on financial security, residence, risk environments, food access, social network, legal status, and education: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5233668/ |

Resources

- Watch the archived webinar series, “Structural Competency: Working Toward Health Equity for Farmworker Patients and Communities,” on MCN’s archived webinars page: https://www.migrantclinician.org/webinar/structural-competency-working-toward-health-equity-farmworker-patients-and-communities

- Access numerous resources about structural competency on the Structural Competency website: https://structuralcompetency.org/structural-competency/

- Learn more about the Structural Competency Working Group and access their curriculum and archived webinars on structural competency for clinicians: https://structcomp.org/

- Read the research that shows its impact in the peer-reviewed article, “Structural Competency: Curriculum for Medical Students, Residents, and Interprofessional Teams on the Structural Factors That Produce Health Disparities”: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7182045