Confronting Immoral Actions, We Can Aim to Stand Up, Not Look On

[Editor's Note: Here on our blog, MCN’s Founder and now Advisor to Witness to Witness, Kaethe Weingarten, PhD, shares stories, resources, and practical actions to support health care workers and others as they encounter the stressors of daily life and the impact of the world around us. Dr. Weingarten's piece for this month is reprinted with permission from MindSite News. MindSite News is a nonprofit, nonpartisan digital journalism organization dedicated to reporting on mental health in America, exposing the problems and failures of the system and spotlighting efforts to solve them. Read the original here, and sign up for the MindSite News newsletter here.]

In this post-election, pre-inauguration period I have one overriding feeling: panic. It is not a loud panic, such that I feel the need to scream, but a quiet, chilling panic, as if I am internally scrabbling to find a path forward that is going to make sense in a hypothetical future that may exist soon. That future is the one in which the new president goes forward with his oft-stated intention to carry out the largest mass detention and deportation operation in American history.

I am not “on tenterhooks.” That old-fashioned expression is defined as being in a state of anxious suspense. I have felt like that before: waiting for exam results, or waiting for labor to begin, to greet an eagerly awaited child. In those cases, I wait passively for something to happen; planned action is suspended.

This is different. I am not waiting passively. I am, in fact, mentally rehearsing possible scenarios and what I will do if they happen. I’m panicky because I cannot decide the best – well, not even a good – plan of action. The scene I imagine is that I am walking down the street heading to the mailbox and I see a National Guard or ICE officer approaching a young woman emerging from a house she has just spent the morning cleaning. In this scenario, I am a bystander, about to be a witness. What I do or don’t do matters.

A bystander is defined as a person who is present at a situation but is an onlooker. In the scenario I imagine, at first, I am the only bystander. In much of the writing about bystanders, the implication is that people are disinterested observers who could influence the situation should they choose to do so. In my imagination, what I do or don’t do will have significance for all three of us at this scene.

Why do I think that? Because for the last 30 years, I have put forward a theory that modifies the idea of a bystander by combining it with trauma theory. In my Witnessing Model, I suggest that a bystander is a witness who is soon to be in one of four different positions, depending on what they do or don’t do.

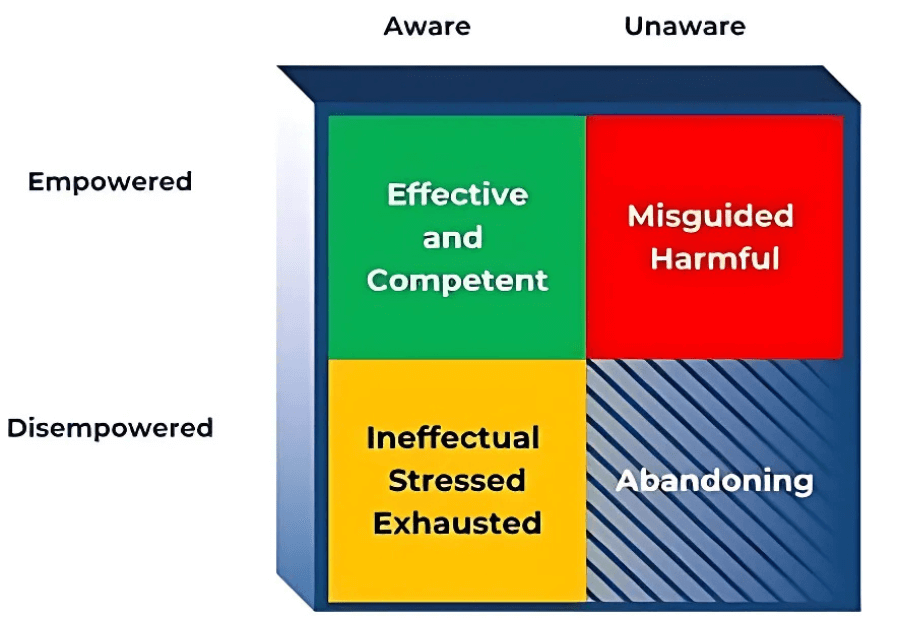

These four witness positions are created by two dimensions: people are aware or not aware and empowered or disempowered.

Our positions vary depending on the situations we witness. Sometimes we can cope with what we witness and sometimes we are overwhelmed.

Position One (upper left) occurs when one is an aware and empowered witness to a situation that is disturbing in some way. Taking action, and having clarity about what actions to take, goes along with the experience of this witness position. A person is likely to feel competent and effective in Position One. Although it is desirable to be in Position One all of the time, no one can be. We work toward it.

Position Two (upper right) may be the position that is most dangerous to others. People who witness violence and violation, for instance, and who don’t understand what they are witnessing, but nonetheless respond as if they know what they are doing, will be misguided. Their actions will be ineffective at best and harmful at worst. The negative impact of witnessing from this position may be far-reaching, particularly if the person witnessing occupies a position of power or is perceived as having power.

In Position Three (lower right), a person cannot register what is truly happening and therefore takes no action to make things better. A witness who is unaware of and thus ignores someone’s urgent need has abandoned that person and the effects may be as harmful as actions taken from Position Two.

Position Four (lower left), may be the most common of all. In this position people are aware of what is going on but are either uncertain what to do or lack the internal or external resources to act in ways that would be helpful – or even to act at all. This position saps energy, enthusiasm and resolve. It can also result in moral distress, an experience in which one feels helpless to take the right course of action. To manage the distress, people often attempt to block out or numb themselves to the situation they face. By doing so they move “over” into Position Three.

In relation to each of these positions, there are short-term and long-term consequences for the self and for the communities of which one is a member.

In my imagined situation with ICE and a neighborhood housecleaner, I am in Witness Position Four, aware of the situation but feeling uncertain about what to do. Research suggests that I am actually more likely to act if I am alone facing this situation than if I am in a group. The failure to act when there is a group has been called “the bystander effect” and it has been written about in the social psychology literature for decades, starting in 1970 with the publication of a book titled “The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He (sic) Help?” released after the murder of Kitty Genovese in New York. At the time, it was believed that several people heard Genovese’s screams but failed to help her.

In that book, the two authors suggest that the presence of others constrains us. First, we may fear that if we suggest a helpful action, we will not be supported, and instead we will be ignored or judged. Second, once we are in a group, our sense of responsibility for taking action diffuses. We may look toward others to observe what they are doing and if they are not acting, we may downgrade our sense that action is urgently required. Finally, if we are with a group and action is delayed, intervention is less likely. Not seeing others act may prompt us to reconsider our own impulse to act and instead see it as misguided, unfounded, foolish or unwise.

Acting, it would seem, requires moral courage. In scenarios like the one I am imagining, there would likely be negative consequences for me if I attempted to intervene between the officer and the woman, even though I am an older, white woman with class privilege. I would hope that I’d have sufficient moral courage to act anyway.

Research suggests that moral courage can be developed with practice. Recently, I read about a method that I think could be helpful to me and others to act with courage. The technique has an unusual acronym: SQUID. The authors present it as a method that helps people become more mindful in a situation that seems wrong so we can slow the process and act more wisely.

- Stop reminds us that when we see something that upsets us, we need to slow down and interrupt our automatic reactions.

- Next, we need to Question what is happening and identify why it seems wrong to us. -The third step is to Understand the wider context of what we are observing that troubles us. A good question might be “What other aspects of the situation should I take into account?”

- Then we need to Imagine what the options are. This likely means it’s important to think about the final goal we want to achieve with our action. This then leads to the final step:

- Decide what to do.

It also helps to act with courage if we have the idea that most people do act altruistically when faced with a person in need. Rebecca Solnit’s book A Paradise Built in Hell details acts of kindness, solidarity and compassion among strangers who are caught up in a disaster. Far from acting selfishly, they found a sense of meaning and purpose in helping others. Altruism is usually defined as a “selfless” concern for others, acting to benefit another with no expectation of anything in return, even if the action results in a personal cost. Yet, the research on altruism makes it clear that there are emotional, physical and social rewards of helping others.

Ordinary people may be inspired to act with moral courage by conceiving of themselves as an upstander – rather than a bystander. An upstander is someone who actively stands up on behalf of others and is not passive or silent in the face of wrongdoing or injustice. The concept has circulated widely in schools to give children who are observers of bullying a set of tools to intervene between bullies and their targets. An upstander is an aware and empowered witness. An upstander is the opposite of a bystander.

In the scenario I have been imagining, I am alone. But if I shift my imagination to include all the people I know and all the people I have never met who think and feel as I do, then I am really in a community of like-minded people – even if at that moment I’m alone on that sidewalk with the officer and the immigrant. I believe that when I act – which I hope I do – I will act alongside thousands of others who are also taking upstanding action in the situations they face. Knowing they are with me may support me to do what I think is right.

We have witnessed shocking immigration scenarios before. In 2018, when I founded the Witness to Witness (W2W) Program, my colleagues and I were outraged and horrified at the news and images of families being separated and children being held in detention facilities. W2W was a way of acting in those cruel times by reaching out to provide support to clinicians, shelter workers, immigration lawyers, journalists and others who were emotionally, and often logistically, overwhelmed by working with immigrants in need. The program’s motto was “the helpers need help.” We quickly learned that all of us who helped the helpers felt better ourselves.

Now, in 2024, W2W remains as relevant and needed as ever. Our Words Matter webinar, blog and video series addresses the health impacts of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies on both immigrants and their allies. As we prepare for the coming years, in which we may see immigration rhetoric, policies, and enforcement that once again leave us horrified, I believe that W2W can provide a roadmap and a community so that people never feel alone when they witness and respond to these types of situations. My scenario situation is hypothetical now, but I can, we can, prepare ourselves.

These are the ideas that will steady me in the perilous times that are likely to come. What are the ideas that will steady you and help you act with moral courage?

- Log in to post comments