Dr. Ed Zuroweste: A Career Serving the Underserved

[Editor’s Note: Happy Anniversary, Migrant Clinicians Network! We continue to celebrate our 35th anniversary with profiles of MCN’s founding members. Here, we chronicle the career of Dr. Ed Zuroweste. Make sure to read last month’s profile of Karen Mountain, MBA, MSN, RN, Migrant Clinicians Network’s Chief Executive Officer.]

“I had no idea I was going to care for farmworkers,” recalled Ed Zuroweste, MD, Founding Medical Director for Migrant Clinicians Network. In medical school, he had not chosen to focus on the underserved rural working class. Yet, his life experiences and circumstances drew him to farmworkers. Over the course of his career, thousands of farmworkers have been able to gain and maintain care and work toward their health and well-being, along with thousands of others around the world. Dr. Zuroweste’s first encounters with farmwork were personal -- and challenging.

“I grew up on a farm in Ohio, and my first paying job -- I worked a lot on the farm for nothing -- was when I was 14. I worked picking strawberries,” he said, working for a young man’s strawberry farm. He worked twelve hours a day. “That was my first entry into what it’s like to do field labor like that: bent over, dawn to dusk. Looking back, that was very helpful in my career working with farmworkers, because I knew exactly what it was like!” He got a second taste of farmwork in college, when he worked two summers harvesting tobacco in Kentucky, where college students worked side-by-side with migrant farmworkers, largely African-American at the time. The college students would compete with what he called the “real” team of farmworkers to unload wagons of tobacco into the drying barns. “We were all athletes and in good shape, but we couldn’t compete with these guys!” he laughed. “I never did any work as hard as those jobs.”

After completing his residency in family medicine, Dr. Zuroweste moved to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and joined a small private practice. On his first day, his second patient was a public health nurse whose job was to travel to migrant farmworker camps to inform farmworkers where the hospital was. “That’s all she did,” he said; farmworkers in the region had few resources for their care.

In his first months as a doctor in Pennsylvania, Dr. Zuroweste saw many farmworker patients. He quickly noticed that they often didn’t return for needed follow-up appointments, so he called the public health nurse for advice. She explained that farmworkers had to work, and daytime appointments were a struggle to attend, so he opened a night clinic at his private practice. “My partners were very tolerant of me doing this,” evidenced by the fact that the practice covered the overhead costs. Dr. Zuroweste felt drawn to the farmworker population, which was clearly underserved and in need of more attention. He found them a joy to work with: “It became the most important part of my practice.”

“I really liked the farmworkers. I liked treating them, I had a lot in common with them, and I got to speak some Spanish,” he recalled. At the time in the early 1980s, most of the farmworkers in the region were African-American or Haitian, but there were increasing numbers of Spanish-speaking workers. During this same time, he learned how the Health Resources and Services Administration provides grant funding for clinical programs to serve farmworkers, and that Pennsylvania’s State Department of Health held the grant for the state. He turned to the department to get funding to set up a migrant clinic out of his private practice. The department agreed, and, in turn, they put him on the state advisory board for the migrant health program. “They made a mistake,” he smiled, “I looked at the finances in the grant, and I realized the state was taking 30 or 40 percent off the top for administrative stuff, and not getting out to the farmworkers.” He knew he could do it better and cheaper -- so, in 1985, he set up a small nonprofit called Keystone Rural Health to run a farmworker program.

Joanne Cochran, who Dr. Zuroweste convinced to be the administrator of Keystone, wrote the initial grant to compete with the Department of Health for the farmworker program grant. They were awarded the funding, and immediately began subcontracting work around the state, while Dr. Zuroweste began seeing patients in his own region under the grant.

Over 30 years later, the tiny nonprofit has grown substantially. Cochran is now the CEO of Keystone Health, a large community health center serving almost 53,000 patients, almost 3,000 of which are agricultural workers served through their statewide migrant program, one of many of its programs to serve patients throughout the region.

Around the same time that he helped to start Keystone, Dr. Zuroweste attended his first national conference on migrant health. In 1984, two nurses and a doctor came up with the idea of MCN, and in 1985, the nascent group had its first meeting during the conference in Seattle, Washington. “We didn’t even have a conference room -- we met in a lobby,” Dr. Zuroweste recalled. Discussing the clinical barriers to serving farmworkers, Dr. Zuroweste discovered that many in the room struggled with the exact same concerns that he had. “We were all just reinventing the wheel. I figured out night clinics, and it was free. But then three farmworkers came in to let me know, ‘just so you know, it’s an insult for you not to charge us -- we want to pay.’ So I decided to charge a small fee, and if they couldn’t pay, they couldn’t pay.” He made up a sliding-scale fee, which others were already utilizing around the country. “I didn’t know this stuff existed until this meeting -- and everyone was dealing with the same issues. That’s where the pillars of Migrant Clinicians Network came up, where continuity of care was so important.” Clinicians shared how patients were lost to follow-up until the following year when they returned to the service area. “We needed a home -- a place where we could share ideas and get together. And tools -- we needed tools, and research. There was no research on anything related to migration and farmwork,” he recalled.

The group settled on having representatives from each of the migrant streams, the routes that migrants took on the West Coast, Midwest, and East Coast as the seasons shifted, to populate a board. “I was talking a lot so they wanted me to be a representative,” he laughed. He declined at first, but agreed to be an alternate East Coast Upstream board member. Board meetings were held in Washington, DC, a relatively short drive from Chambersburg, so he attended every single board meeting for two years. At the end of those two years, in 1987, he was elected to the board. The all-volunteer board established policies and procedures, developed tools and resources, and compiled a directory of health centers. “One of our jobs as stream coordinators was to call every single medical director, every quarter, in our stream area. It took hours and hours! And then we finally hired Karen,” he said. Karen Mountain, MBA, MSN, RN, was MCN’s first paid staff person, and its first and only CEO. Her attention helped make the board members’ work more manageable. After several years of volunteer work, Dr. Zuroweste joined MCN as its first Medical Director, helping to develop Health Network along with Deliana Garcia, MA, MCN’s Director of International Projects and Emerging Issues. He also supported MCN in its early days to develop numerous resources to help fellow clinicians feel connected, supported, and successful in their work serving farmworkers and other migrants.

[Laszlo Madaras, Ed Zuroweste, and Candace Kugel at dinner with Keystone Health staff]

Meanwhile, his role at Keystone was growing. By 1992, Keystone had expanded significantly. It was funded as a community health center serving, not only farmworkers, but the entire underserved community. Dr. Zuroweste left his private practice to become Keystone’s Medical Director. Candace Kugel, FNP, CNM, MS (who later became MCN’s Specialist in Clinical Systems and Women’s Health) and Mary Englerth had already been hired to start the new community health center while Dr. Zuroweste transitioned from his private practice. Soon after, Laszlo Madaras, MD, MPH, joined the small group of clinicians. (Dr. Madaras eventually became MCN’s Chief Medical Officer, taking over for Dr. Zuroweste in 2017.) Meanwhile, the migrant farmworker population in the region was shifting after a nursery supply company moved in, bringing its workers, who were largely Guatemalan, with it.

At the same time, Dr. Zuroweste was offering a rural health elective for Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. In 1999, Dr. Zuroweste and Kugel began bringing students as part of an international rural health elective to Honduras, to a mountain town with little access to health care. Over the next two decades, Dr. Zuroweste and Kugel, sometimes accompanied by Dr. Madaras and his family, visited the mountain region over thirty times with students. The region now boasts two full-service clinics, and many of the families stay in close touch with Dr. Zuroweste and Kugel. As with much of his other work, Dr. Zuroweste felt inspired and invigorated by global health work -- and ready to take on more.

“It was that kind of work that got me into the WHO stuff,” he said. Through a contact with the World Health Organization, Dr. Zuroweste went to Geneva for five months in 2009 to help develop a manual for small hospitals and clinics in low-resource countries that contained protocol and best practices for various diseases. Dr. Zuroweste was tasked to re-write the chapter on influenza. This was during the terrifying rise of H1N1, the influenza strain that many feared would turn into a worldwide epidemic. He, with a team of three other WHO physicians, developed accompanying teaching modules. He then logged over 180,000 miles, traveling the globe to provide trainings, lectures, and updates on H1N1.

In 2014, he was invited back -- this time to help a team of WHO physicians adapt those H1N1 training modules for the management of patients during the Ebola crisis. “I went to Uganda, and did a train-the-trainer workshop. We trained 100 African physicians… Then I went to Guinea and Sierra Leone, and, with two other WHO physicians, taught over 200 Cuban doctors to be able to work safely in Ebola treatment centers. We had it translated, and we taught it in Spanish for the Cubans,” Dr. Zuroweste said.

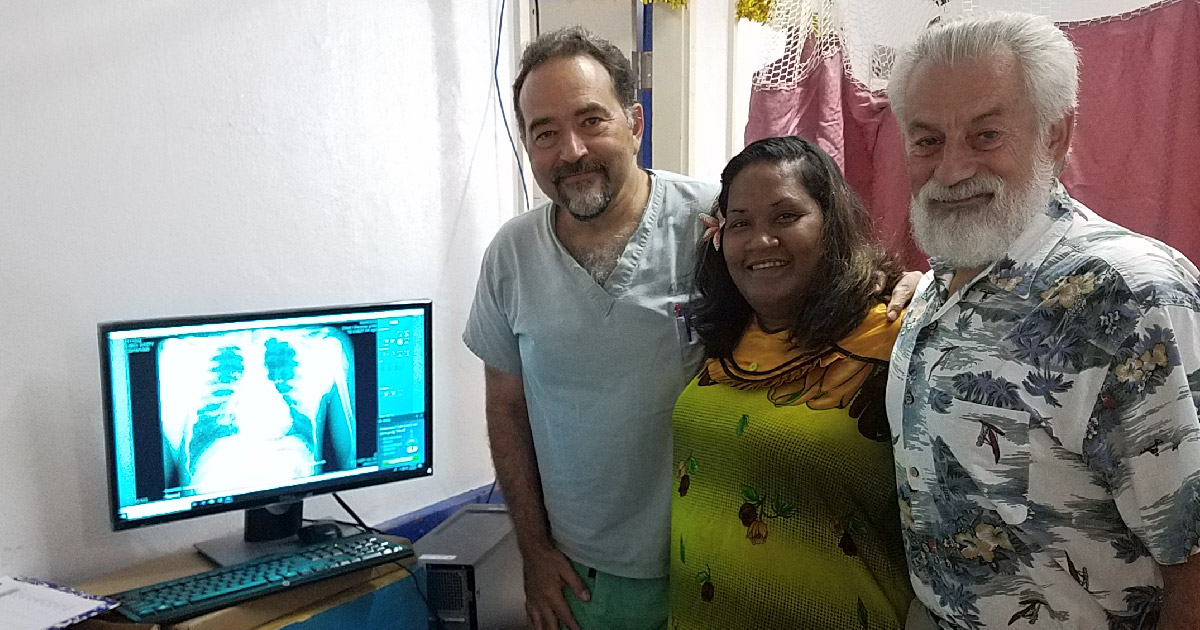

His international work expanded in March 2017, when he joined a large team of physicians and nurses to participate in a CDC/WHO project to screen all 6,000 adults on the small island of Ebeye in the Marshall Islands for tuberculosis, leprosy, diabetes, and hypertension. He returned to the Marshall Islands in August 2018 along with Dr. Madaras, by then MCN’s Chief Medical Officer, for a similar but even larger project to screen over 24,000 individuals on the island of Majuro. He and Dr. Madaras are making plans now to participate in 2020 in another similar massive TB screening project, this time on the small Micronesian island of Chuuk.

[Laszlo Madaras and Ed Zuroweste in the Marshall Islands screening for TB, leprosy, diabetes and hypertension]

Throughout these years of work in migrant, farmworker, and global health, Dr. Zuroweste was also battling infectious disease at home. In 1986, he saw his first patient with what would later be known as HIV. “Since Chambersburg at that time had no infectious disease specialists and since we were also seeing a lot of patients with TB and HIV, I had to educate myself in these infectious diseases in order to provide proper care for our patients,” he recalled. In the early 1990s, Dr. Zuroweste took over the position of TB clinician for the local health department’s TB clinic, a position he still holds today. He was fascinated with TB and was determined to learn as much as he could to better provide this specialized care to his patients. He currently is the attending physician caring for all of the TB patients in eight Pennsylvania county health departments, and in 2013 he was hired as the TB Medical Consultant for the Pennsylvania Department of Health responsible for consulting on all complicated cases, writing and approving clinical guidelines and quality assurance for all of the TB cases in the state.

Over the course of his fascinating career, Dr. Zuroweste has taken numerous jumps into treating infectious disease, promoting global health, and supporting farmworker health, often as his community has dictated, but always with a deep interest in serving most fully and attentively. “It was thrown in your lap, and you have to adapt, and I was interested, so I read and read and learned and learned,” he said, speaking specifically of his TB work. Now, in 2019, Dr. Zuroweste is still engaged on each of these fronts. As MCN’s Founding Medical Director, he still engages weekly with the Health Network team and supports MCN as needed, although much of his work has transitioned to Dr. Madaras. He just renewed his position as Assistant Professor at Johns Hopkins through 2020. He continues to see patients in Pennsylvania with TB every month. And he plans to go to Honduras with medical students again in February 2020. Meanwhile, thousands of people -- farmworkers in Pennsylvania, rural residents in Honduras, influenza and Ebola survivors across the world, people recovering from TB, and those served by MCN’s Health Network -- have better health, thanks to Dr. Zuroweste’s efforts over the years.

MCN is overjoyed to announce the launch of the Kugel & Zuroweste Health Justice Award!

Join us in honoring Candace and Ed, and encouraging new leaders to continue the vital fight for health justice by donating to the effort.

Like what you see? Amplify our collective voice with a contribution.

- Log in to post comments