Avian Flu on Dairy Farms: What Clinicians and Dairy Worker Patients Need to Know

Highly pathogenic avian influenza has arrived in dairy farms in eight states across the United States in recent weeks. One dairy worker became infected with avian flu when the virus jumped from the cows to the worker; luckily, his symptoms were mild. After two years of avian flu wrecking havoc on poultry production, there is concern that it may now harm the dairy industry. The CDC Health Advisory from April 5th gives a full description of the event as well as detailed recommendations for clinicians, including isolation and notification steps if a patient has signs and symptoms compatible with avian flu. As always, we have our eye toward the health and well-being of the workers, seeking to provide clinicians who serve these workers up-to-date and useful information, so they can best equip workers in the early stages to prevent further spread and to answer questions to reduce fear and confusion.

Jeff Bender, DVM, MS, DACVPM, is a veterinarian with the University of Minnesota’s Veterinary and Public Health School, and Director of the Upper Midwest Agricultural Safety and Health (UMASH) Center, also housed at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Bender’s expertise lends unique insight into both emerging health concerns of farm animals, and the occupational and environmental health needs of the workers who care for those animals. Here, Dr. Bender speaks with Migrant Clinicians Network’s Claire Hutkins Seda about the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in dairies and what clinicians need to know. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

People are throwing around all sorts of terms for this influenza. Some people are calling it highly pathogenic avian influenza or HPAI, some are calling it bird flu, others avian flu…

Dr. Bender: To even add more controversy to it, there's now the term ‘cattle influenza.’ It is a highly pathogenic avian influenza -- we know that because it kills poultry and it does so in large numbers. It's [also] H5N1 and that just refers to the structure of the influenza virus.

We’re now seeing this avian flu in cattle in seven states. And, in the last few years, we’ve seen not just poultry, but wild birds, and also many other wild animals that have contracted it. Is this a new thing, the transmission among animals that aren’t birds?

Dr. Bender: What's really interesting is that H5N1 has been circulating for over 20 years. In fact, the first detection in the globe was in 1989… People were getting sick after exposure to birds. The virus had stayed in the eastern hemisphere -- it had never really crossed over – but, as you know, a couple of years ago it did arrive here, because migratory bird patterns cross, especially at the Arctic and Antarctic, so there's a chance for birds to mix from different hemispheres and as well as for viruses to mix. H5N1 has really emerged these past couple of years, and influenza viruses, they change all the time, they adapt. So one of the [ways] that it has been adapting over the last couple of years is this spillover into mammals. And we just didn't see that [previously]. So, it was primarily [detected among] birds, and then last year, [we] saw a lot of raptors -- eagles and owls and hawks -- that were becoming ill and so, again, it was spilling over into different bird species, as well as mammals… Now, this detection that we're starting to see in cattle, and this spread across the United States, is actually a novel and emerging issue.

What does this mean for surveillance on dairy farms? It seems to me that our surveillance systems are working, as we have identified the illness.

Dr. Bender: [Dairy farmers with sick animals] have to raise the index of suspicion. So [first is] the importance of having a surveillance system in place, and then also to know who to talk to if you see something unusual. Those are the two critical pieces and I think why we've been able to see this emerging issue.

And who do you talk to, if a dairy farmer sees something unusual, has a sick cow?

Dr. Bender: For a producer, they're going to say, ‘My cows seem to be off. They're not producing as much milk. The milk is discolored.’ So, first, obviously, is going to your veterinarian. And then as the veterinarian sees this, they have resources either through diagnostic laboratories or the state veterinarian or animal health officials for that state.

That’s helpful, because I think people are wondering about the process, how we as a country are making sure that we're staying safe. But there’s the added question of the safety of the workers. We have seen two farmworkers who have gotten ill. This most recent worker was working on a dairy farm – luckily, his symptoms were very mild. As you know, we serve clinicians who are working very closely with dairy farmers and other farm workers. What should they be watching out for?

That’s helpful, because I think people are wondering about the process, how we as a country are making sure that we're staying safe. But there’s the added question of the safety of the workers. We have seen two farmworkers who have gotten ill. This most recent worker was working on a dairy farm – luckily, his symptoms were very mild. As you know, we serve clinicians who are working very closely with dairy farmers and other farm workers. What should they be watching out for?

Dr. Bender: Right. So, this avian influenza outbreak has been occurring for the past couple of years, and we've had two individuals, one that was exposed to poultry in Colorado and then another individual, just this month, that was diagnosed after being exposed to cattle. Both of them were mild [cases].

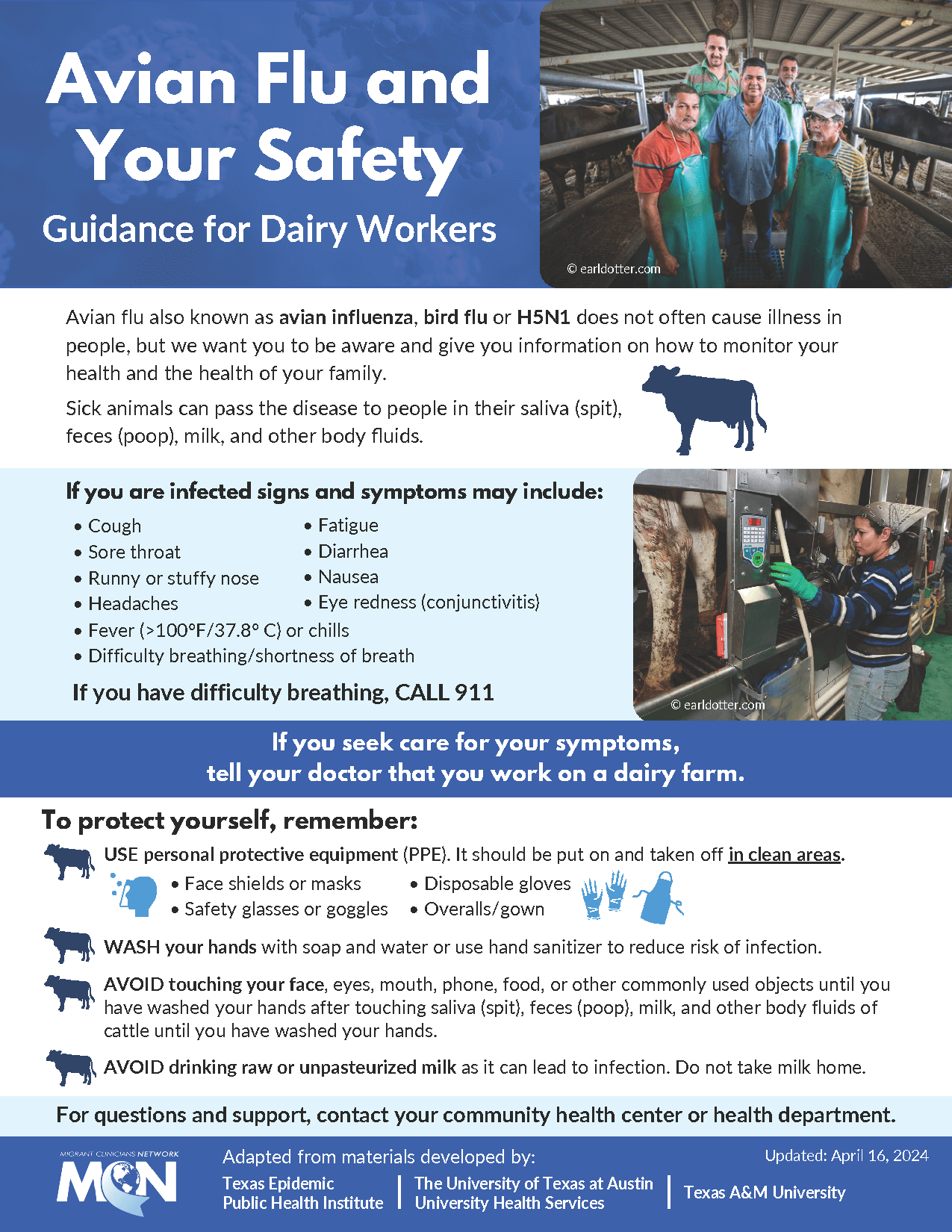

One of the obvious questions is, what kind of symptoms can this have? It’s generally flu-like symptoms. So, basically, that's what clinicians and health care providers need to be looking for: cough, fever, joint pain, muscle aches, and conjunctivitis or redness of the eyes as being some [symptoms] that we've seen with some of these zoonotic influenzas, these animal-to-human influenza strains.

So that's what that index of suspicion should be, but also the importance of the history: Are they working on a farm? What kind of farm is it? Were there sick animals, and were they exposed to them? What were their job tasks – ‘I was taking dead cows out to the field,’ or ‘I was removing the dead birds from the barn’ – these help the clinician understand the type of exposure, [address] the symptoms, and then contact appropriate authorities that will help guide with diagnostic tests and appropriate follow-up and treatment recommendations. Oftentimes, you'll get that [guidance] through the state health department.

What are the steps that clinicians can do to prepare, as we watch this situation develop?

Dr. Bender: Continue to build bridges with producers so that they feel comfortable coming to us with their health concerns or questions. I saw that a fair amount with COVID and COVID response -- producers were starting to reach out saying, there's a lot of anxiety for my workers, they're really uncomfortable, they have a lot of questions regarding personal protective equipment and those type of things. So I think building bridges is probably one of the key things that we need to continue to do.

The other thing that we can really help with is to provide some guidance regarding precautions:

What are the risks? What situations are riskier? And what things they can do to protect themselves? An obvious question is, what should be the normal personal protective equipment that I should be wearing?

When you think about dairies, you know, cows poop and pee a lot. And so there's a lot of splashing. [There] may not be influenza, but cow poop can have a lot of other things, like E. coli and Salmonella and Campylobacter. So, how do I protect myself? Do I have some coveralls so that I'm not getting wet? How do I keep the manure out of my mouth and off my face? And now, with milk, the concern is, could there be influenza in the milk? So, [do I need] gloves, do I need to wear a face shield, so I don't get splashed on my face? Those are constructive conversations that our clinicians can start to have with producers.

Do you expect to see the virus becoming a concern in the coming months among farm workers and dairy workers, given what we know right now?

Dr. Bender: The Centers for Disease Control, they really consider this a low risk… those who have come down with infections globally are those who are working with diseased, sick, or dead animals. But, we need to be observing and watching this because this virus has changed and so we need to kind of monitor that and see if there’s a chance for person-to-person spread or more severe illness. So, those are some of the things that we need to make sure that we have in place. But at this point, the risk seems to be low. We're taking some precautions, we're trying to identify those ill animals and quarantine those animals and for the case of poultry, they often are culled or removed [to prevent] further spread.

Thank you – I know that’s a tough one, to try to predict!

Dr. Bender: Yes, the crystal ball! You know, I wouldn't have guessed that cattle would have picked up influenza A, so that's why it's an emerging issue and something that we need to monitor. And there are a lot of unknowns. [For example, cows] shed the virus through their mouth, but how much virus is in the mouth? Is there cow-to-cow transmission? There's been a lot of speculation. And so, I'm always a little bit nervous about these early phases of an outbreak because a lot of things get postulated but, really, we need the good epidemiology to understand what's happening on the farm and what are the risks to the cattle and to the people that are working with those cattle.

Dr. Bender: Yes, the crystal ball! You know, I wouldn't have guessed that cattle would have picked up influenza A, so that's why it's an emerging issue and something that we need to monitor. And there are a lot of unknowns. [For example, cows] shed the virus through their mouth, but how much virus is in the mouth? Is there cow-to-cow transmission? There's been a lot of speculation. And so, I'm always a little bit nervous about these early phases of an outbreak because a lot of things get postulated but, really, we need the good epidemiology to understand what's happening on the farm and what are the risks to the cattle and to the people that are working with those cattle.

On that same line, in considering what clinicians who are serving dairy farm communities need to think about right now, one of the things we've been talking about internally is that sometimes dairy workers take milk home. And oftentimes that milk is unpasteurized. Is there anything you want to say about that? I would guess I know your answer, but…

Dr. Bender: It's going to be probably pretty obvious, yeah! Actually, that is one of the strong recommendations: the fact that this virus is being shed in the milk and we really don't know, can we transmit it in the milk? And so it's yet another reason to not drink raw milk. There's a number of things that can be transmitted in raw milk, and so, I'm not a big proponent of raw milk consumption. I think pasteurized milk is the best way to go. Pasteurized cheese is, is the best way to go, the safest. We know that people are taking milk out of the bulk tank, maybe taking it home, maybe making cheese with it… but really there is a potential risk, so that's actually one of the recommendations for farm workers.

One is to be aware of what this [virus] is. Two is to take precautions, when you're working on the farm, and then three is to avoid raw milk.

We talked a couple of years ago about the mental health consequences of bird flu for workers, and I'm thinking about that same issue today, particularly around the culling of animals, but also the stigma of coming from infected farms, and the possibility of getting ill, of course, is scary. Then on top of all of that, many of these farm workers and dairy workers have fear of exposing their immigration status or of losing their job. What do clinicians need to be thinking about in terms of mental health?

Dr. Bender: Unlike with poultry, we don't see deaths in cattle. The cattle are just taken off production for a number of days. So, hopefully, [dairy workers won’t be] dealing with mass culling and the emotional and psychological impacts.

However, there's a fair amount of anxiety when you're working and you're [wondering], is this is this something I need to worry about? Is this something that might be on my dairy? Am I going to get this strange new disease? So that has to be a conversation. This is actually where our clinicians can probably help our producers: how do you have those conversations about what the risk is? Clinicians can provide that guidance as to how to support the mental health of those workers, [to manage] their anxiety, which they may not overtly share with [their clinicians] or be worried about sharing. This is probably where we need to take some responsibility of engaging those producers and saying, you know, your workers might be nervous about this… Workers may wonder, ‘Is there going to be a government official that's going to come and talk to you about the farm? And is there risk there?’ Will the workers be provided guidance – as to, ‘I'm not feeling really well, I was around a sick cow. Should I get tested?’ [and they need] comfort around being able to access health care as well as get the appropriate diagnostic tests, while also, not have to worry that ‘I'm going to get reported and deported in in the process.’ So, yes, I think that especially your clinicians are more astute to these factors. And I think they can continue to serve as educators for other health care providers especially in rural communities.

Resources

Avian Flu and Your Safety: Guidance for Dairy Workers

Available in English and Spanish

Avian Flu and Dairy Workers: What Clinicians Need to Know | Q+A Videos

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s April 5th Health Advisory includes a list of recommendations for clinicians and steps to take if a patient has signs and symptoms compatible with avian influenza. We highly recommend reviewing and sharing the advisory.

- UMASH’s Safeguard your farm: Protect you and your livestock from HPAI

- MCN’s 2022 blog post with Dr. Bender, The Trauma of Avian Flu: What Workers Need

- Log in to post comments